August 6, 1945

I was in my first year of junior high school.

At 8:15 a.m.

A single atomic bomb was dropped onto the city of Hiroshima.

That day, my classmates had gone out to work

pulling down buildings.*

There were 192 of them.

All of them died.

The Nakajima Shin-machi neighbourhood was about 600 metres from the hypocentre.

Scorched by the heat and thrown by the blast,

their faces were unrecognisable.

August 6, 1945

I was in my first year of junior high school.

At 8:15 a.m.

A single atomic bomb was dropped onto the city of Hiroshima.

That day, my classmates had gone out to work pulling down buildings.*

There were 192 of them.

All of them died.

The Nakajima Shin-machi neighbourhood was about 600 metres from the hypocentre.

Scorched by the heat and thrown by the blast,

their faces were unrecognisable.

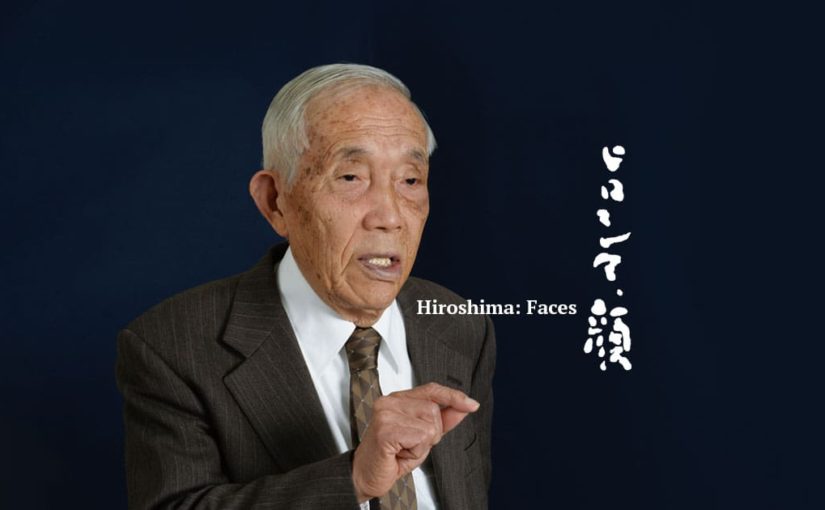

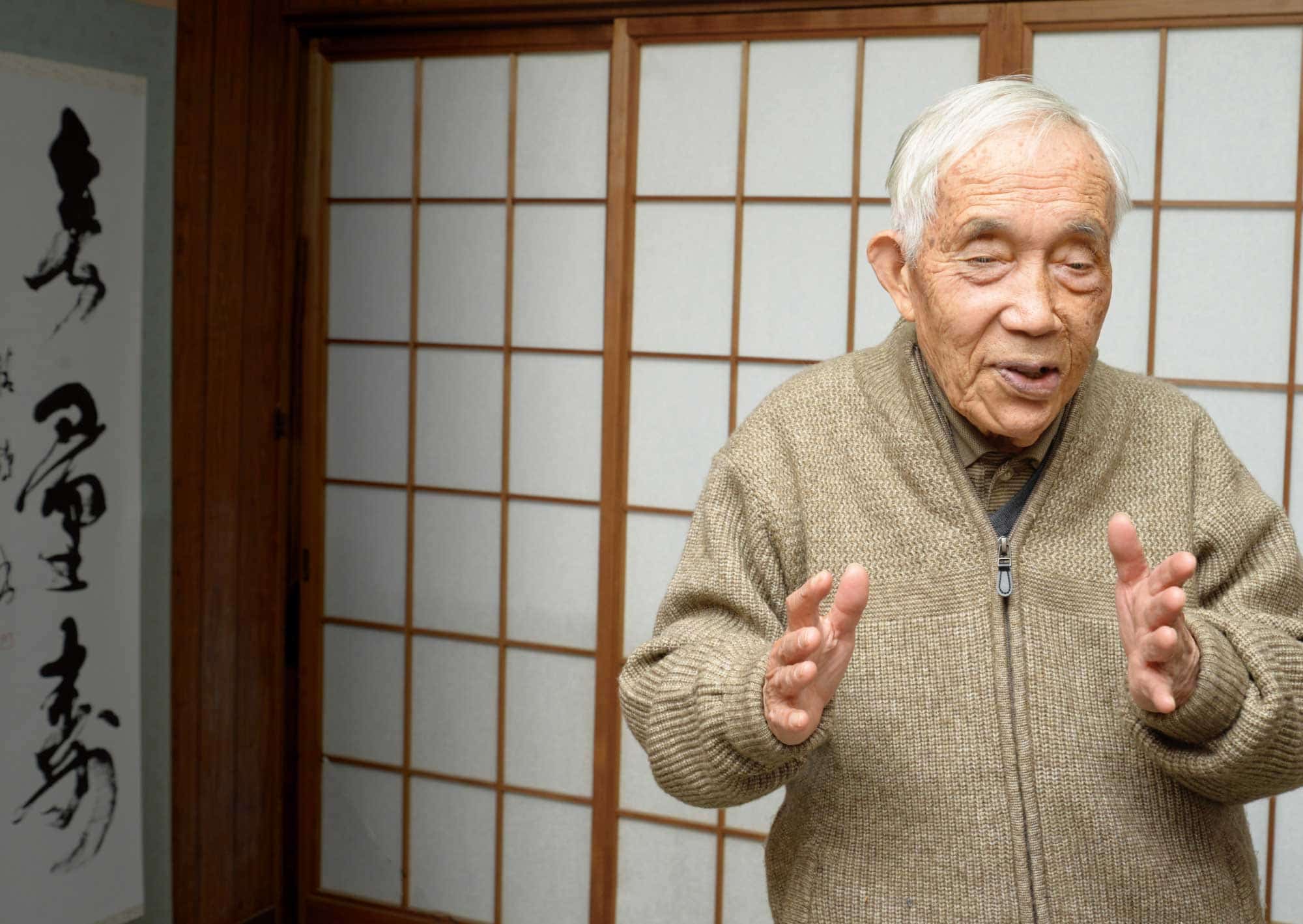

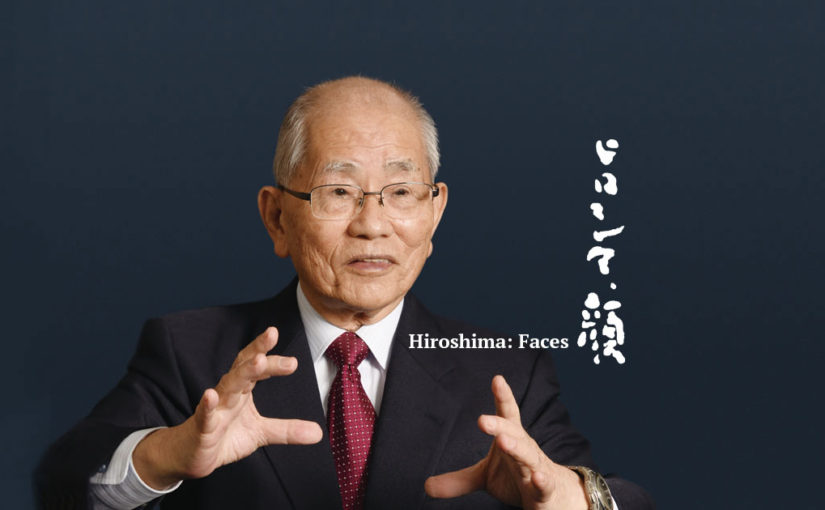

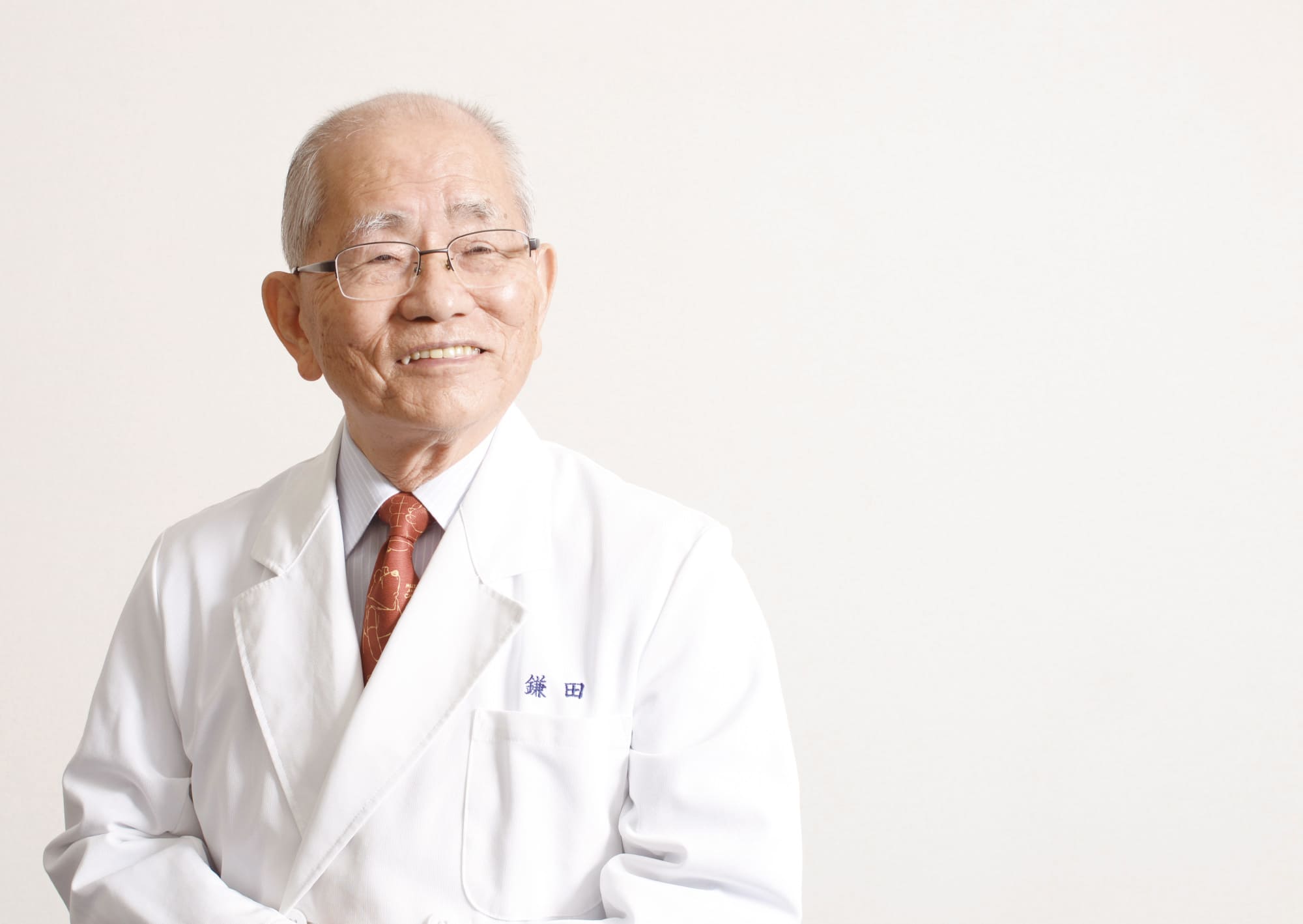

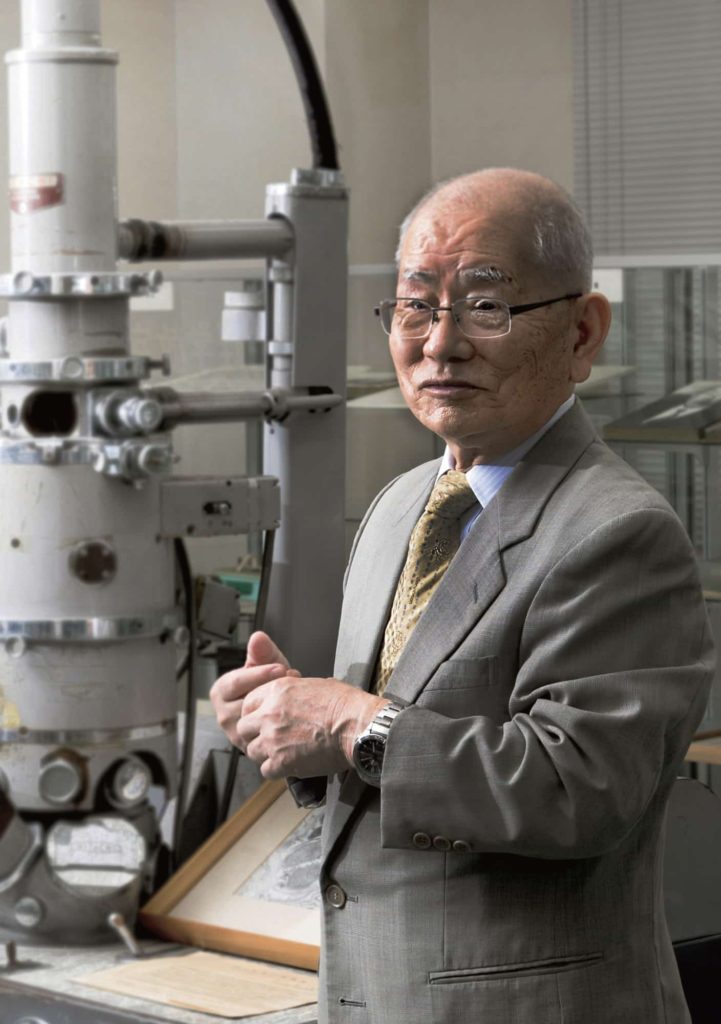

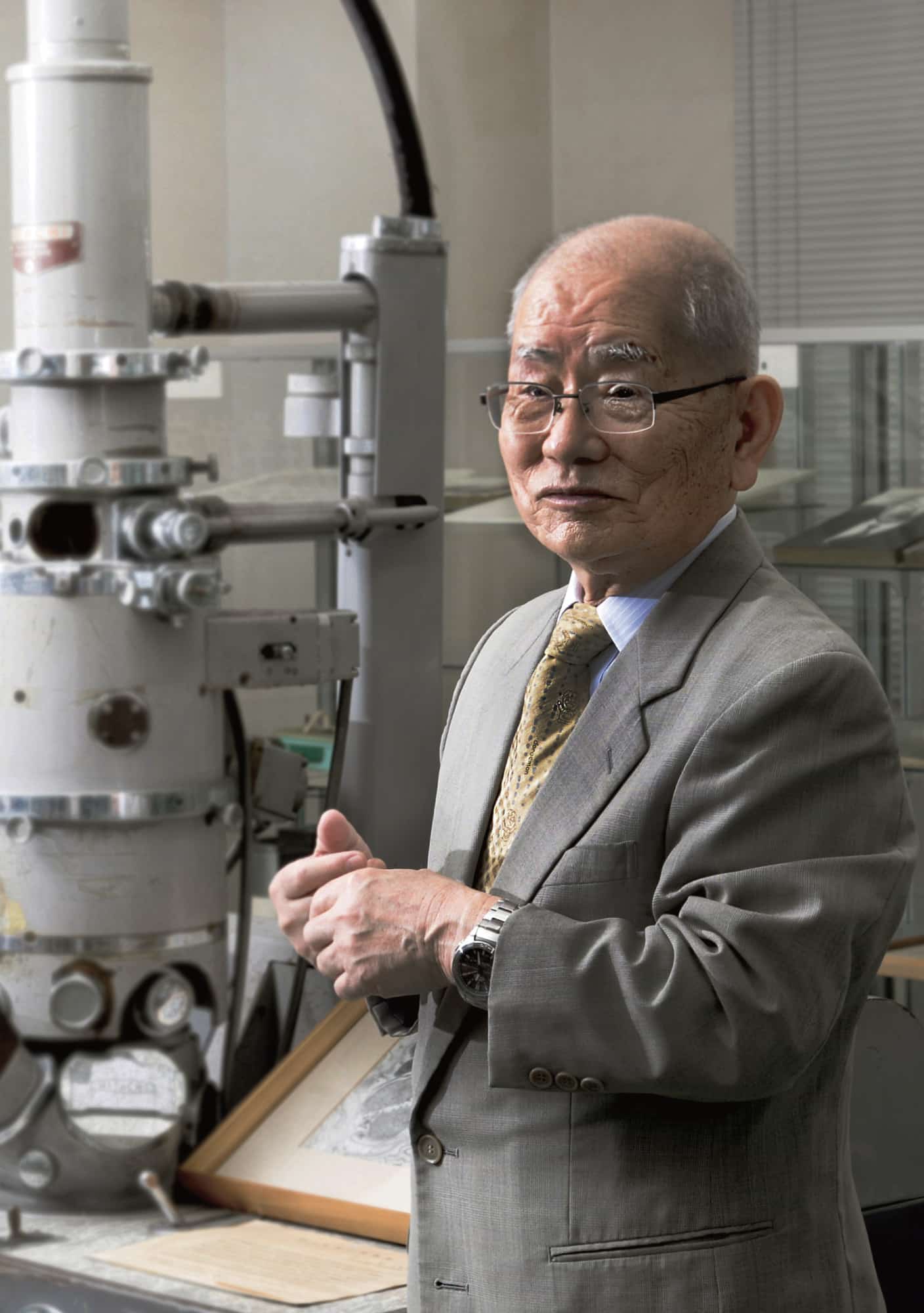

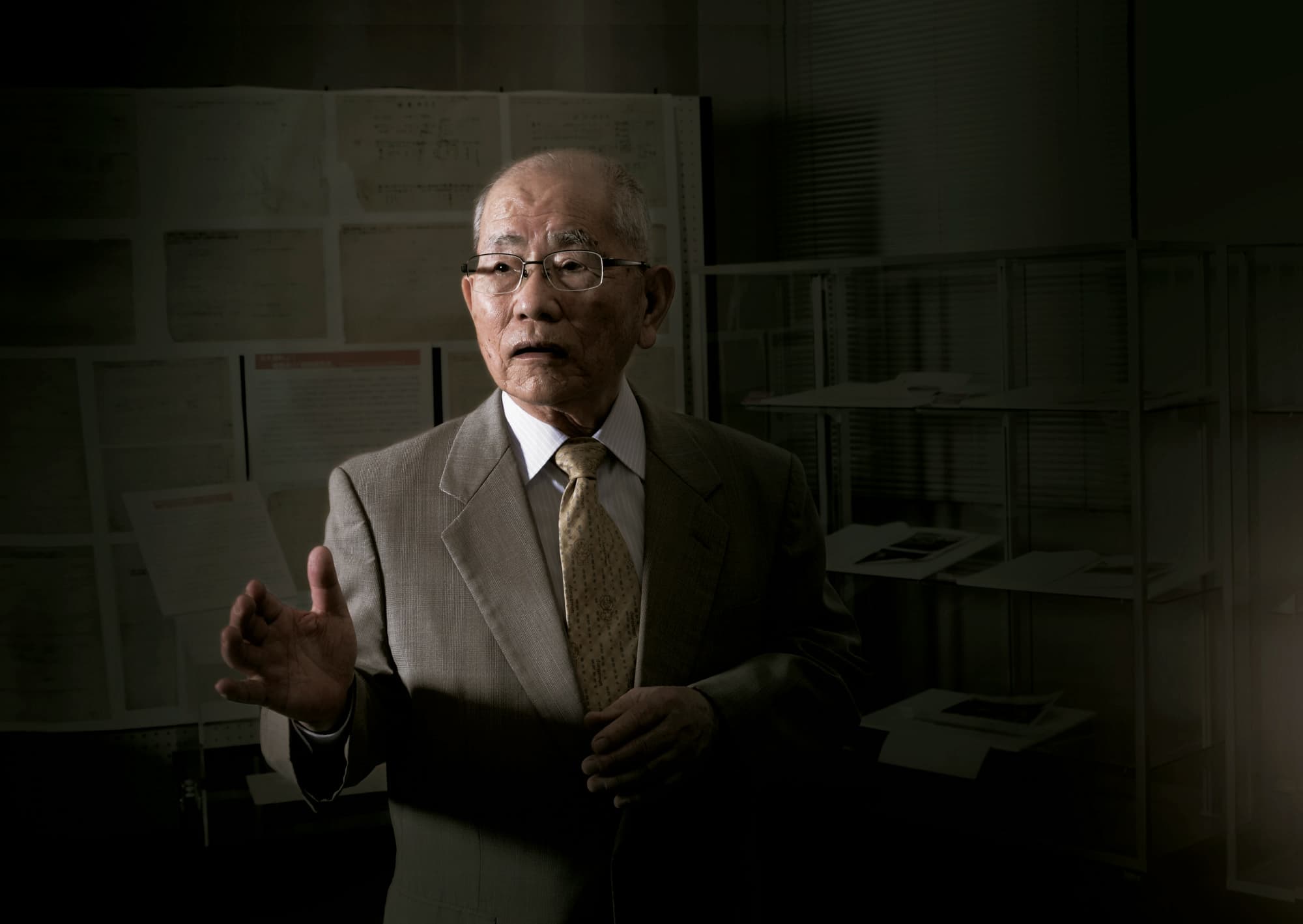

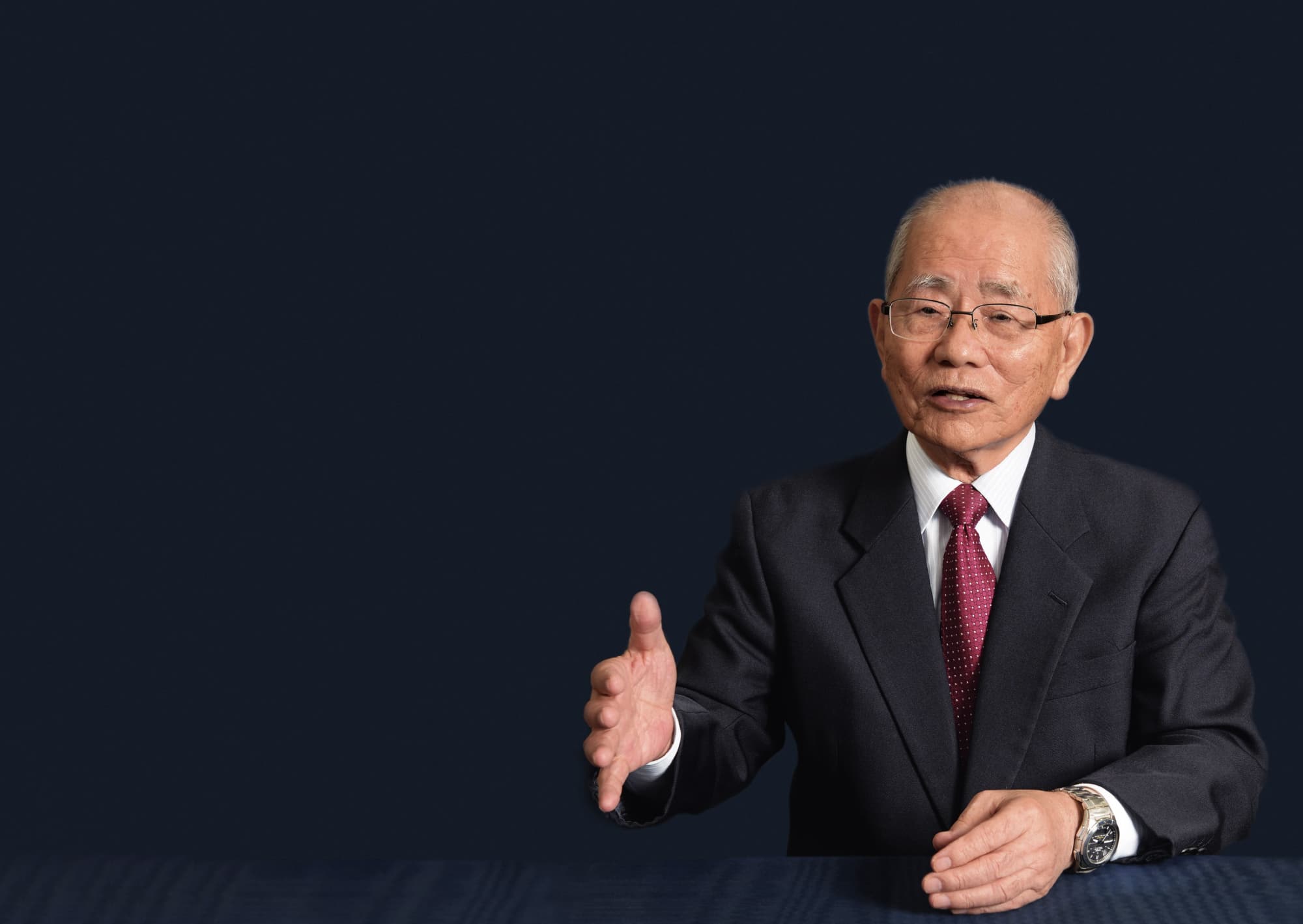

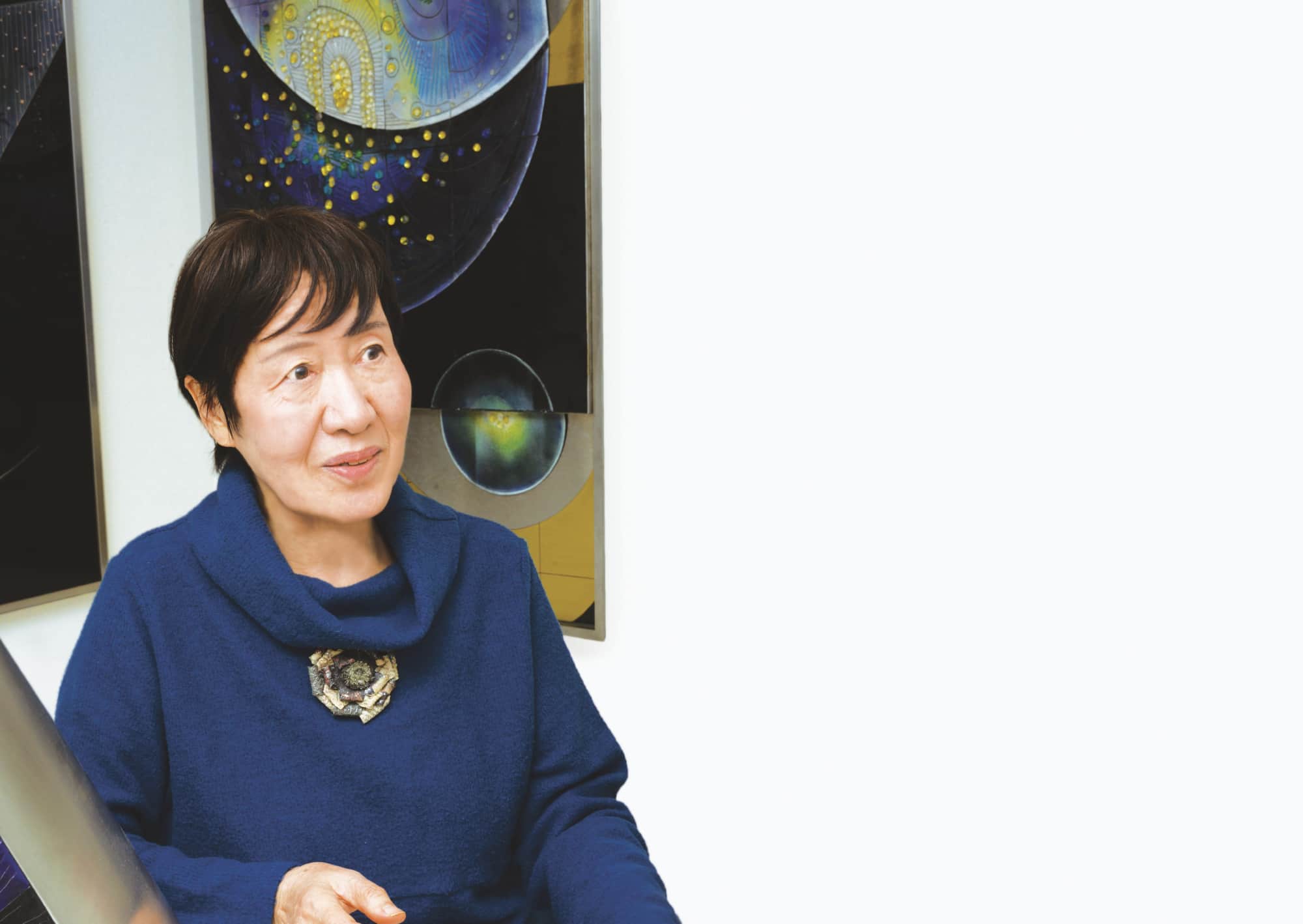

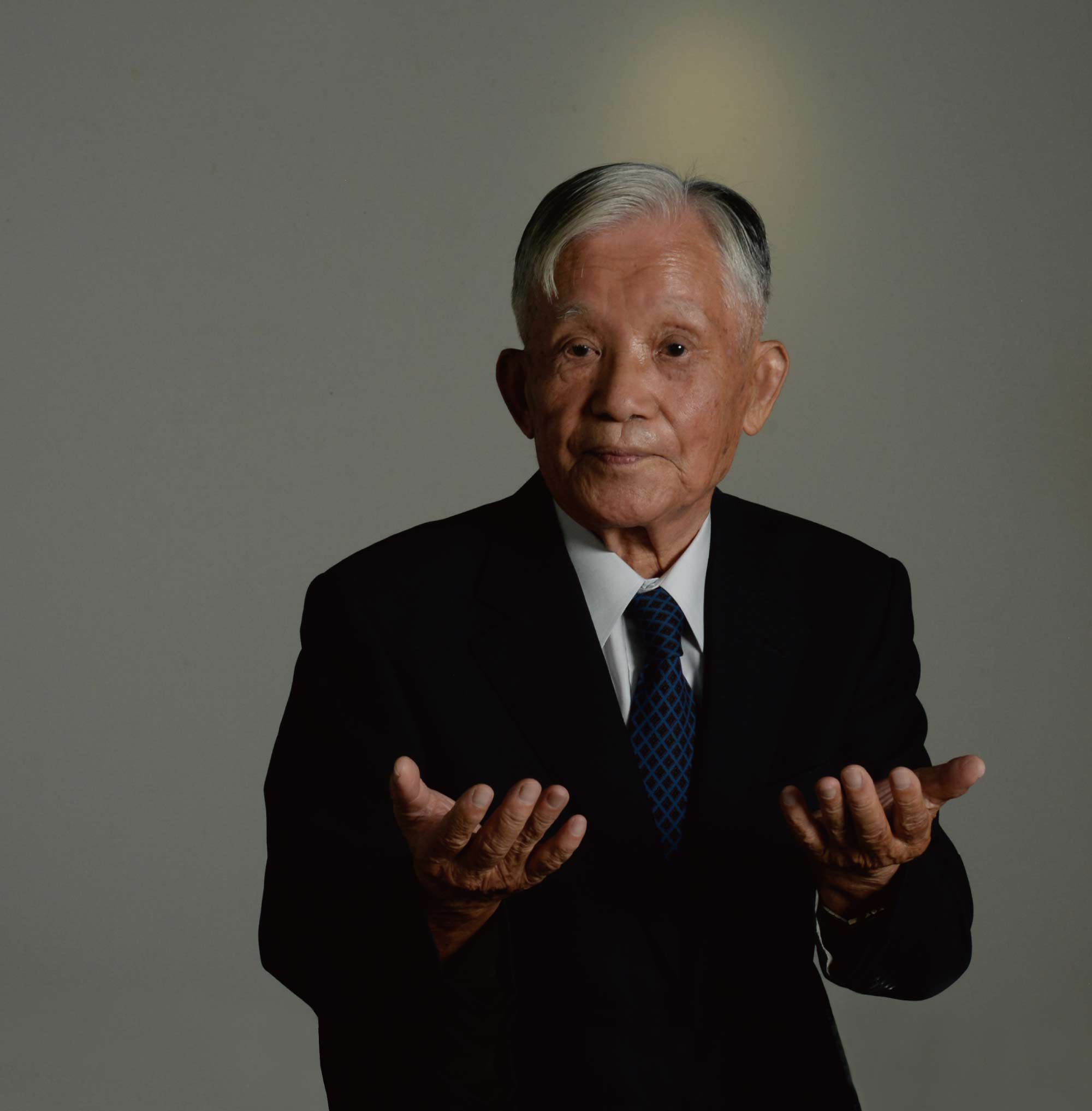

Profile

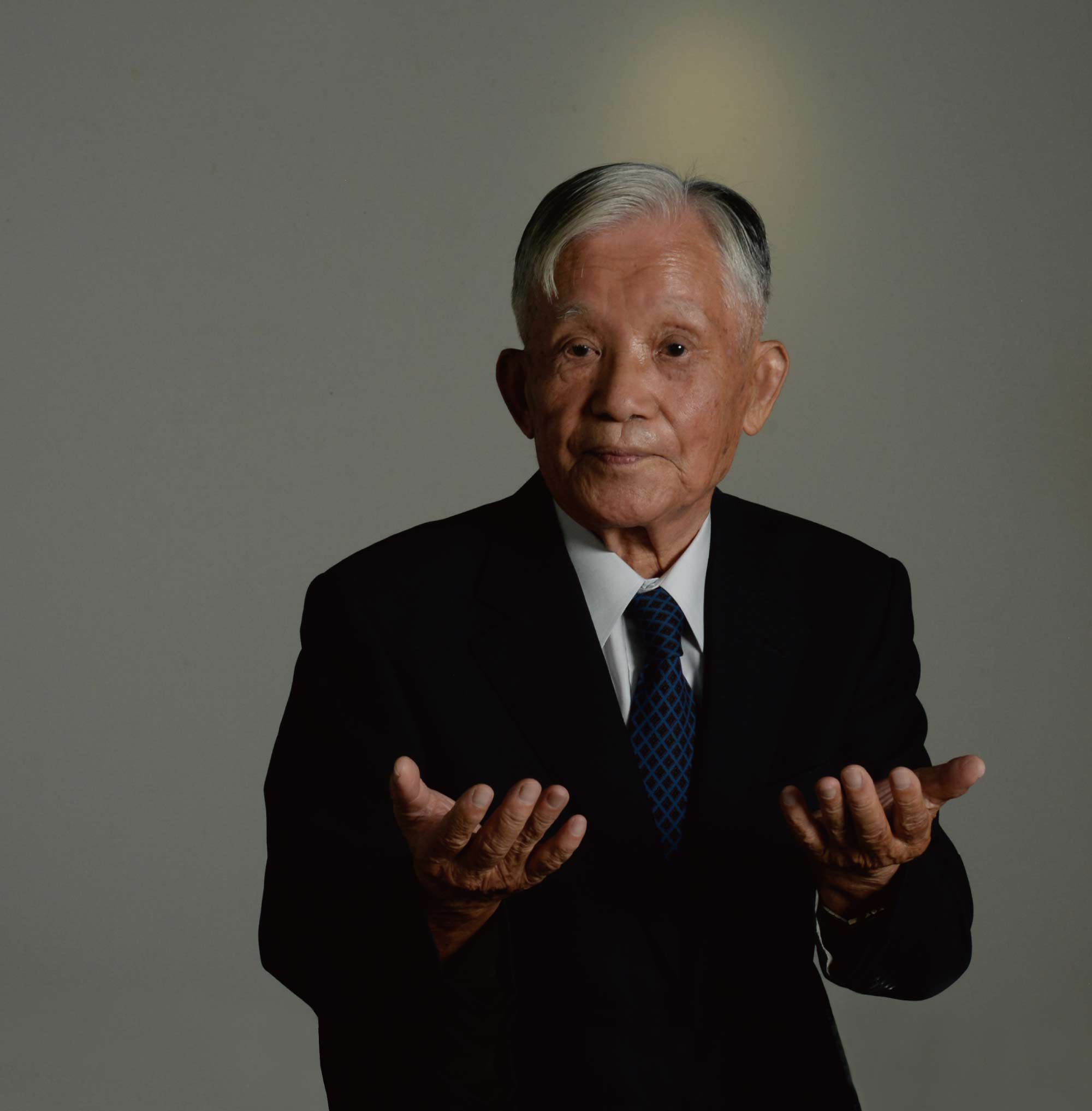

Seigo Nishioka

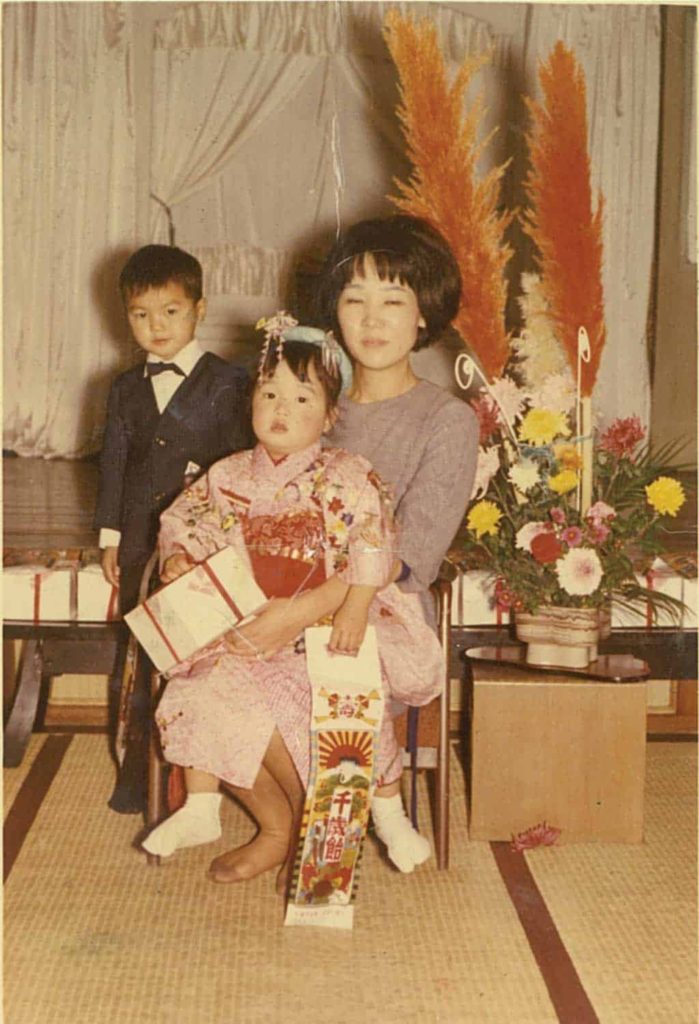

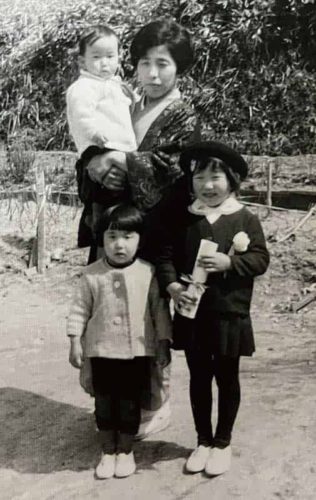

orn on October 25, 1931, in the Minato Ward of Osaka City, Mr. Nishioka later moved to the Nishi-Hakushima-cho. Including his parents and two older brothers, he was the youngest of three children in a family of five. Despite the hardships of life during wartime, his life was filled with the love and affection of his family.

In 1945, Mr. Nishioka enrolled at Hiroshima Prefectural Technical School (now called Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical High School). On August 6, he was not feeling well, so he took the day off from his work demolishing buildings in the Nakajima Shin-machi district of the Naka Ward, about 600 metres from the hypocentre. Instead, Mr. Nishioka headed to his school in Senda-machi (about 2 km from the hypocentre) to do some work there. Little did he know that his fate was at a crossroads. As he entered the school gates, he heard the faint roar of a B-29.

“I thought, that’s strange, the air raid warning had been lifted,” he said.

Every one of his classmates who had gone to work demolishing buildings that day died. Mr. Nishioka himself suffered injuries and burns to his face and body. Initially, he went to a relief camp at Koryo Junior High School before moving to a camp in Sakamura on August 9. On August 15, he arrived at a relative’s house at his father’s hometown on Ikuchi-jima Island.

“Blood had soaked through the bandages wrapped around my entire head and maggots crawled out of the wound. The people around me avoided me,” he said. His family and relatives, who had been told that all the first-year students in his class had died, said that they thought he was a ghost when they first saw him.

With the generous and kind nursing care that he received from his relatives, Mr. Nishioka gradually recovered. While living a difficult life in his mother’s childhood home, he obtained a scholarship to continue his studies. Upon entering the workforce, he pursued a career in design and power plant work. Amid his 35 years of work, he married and had two children. He has suffered from various illnesses such as acute pancreatitis, liver damage, inflammation of the gallbladder, and intestinal obstruction, all for which he has been in and out of the hospital repeatedly for surgeries. He has also produced a kamishibai story titled, “A Thirteen-year-old Boy’s A-Bomb Experience.” From 2019, Mr. Nishioka’s story, along with the clothes he was wearing at the time of the bombing, has been displayed in the newly renovated East Wing of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Although he lives happily, surrounded by his two sons, their wives and his five grandchildren, he has never forgotten his friends and the citizens of Hiroshima who came to such a cruel end at the hands of the atomic bombing. He continues his activities to pass on his experiences of the war and the atomic bombing to the next generation.

Profile

Seigo Nishioka

Born on October 25, 1931, in the Minato Ward of Osaka City, Mr. Nishioka later moved to the Nishi-Hakushima-cho. Including his parents and two older brothers, he was the youngest of three children in a family of five. Despite the hardships of life during wartime, his life was filled with the love and affection of his family.

In 1945, Mr. Nishioka enrolled at Hiroshima Prefectural Technical School (now called Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical High School). On August 6, he was not feeling well, so he took the day off from his work demolishing buildings in the Nakajima Shin-machi district of the Naka Ward, about 600 metres from the hypocentre. Instead, Mr. Nishioka headed to his school in Senda Town (about 2 km from the hypocentre) to do some work there. Little did he know that his fate was at a crossroads. As he entered the school gates, he heard the faint roar of a B-29.

“I thought, that’s strange, the air raid warning had been lifted,” he said.

Every one of his classmates who had gone to work demolishing buildings that day died. Mr. Nishioka himself suffered injuries and burns to his face and body. Initially, he went to a relief camp at Koryo Junior High School before moving to a camp in Sakamura on August 9. On August 15, he arrived at a relative’s house at his father’s hometown on Ikuchi-jima Island.

“Blood had soaked through the bandages wrapped around my entire head and maggots crawled out of the wound. The people around me avoided me,” he said. His family and relatives, who had been told that all the first-year students in his class had died, said that they thought he was a ghost when they first saw him.

With the generous and kind nursing care that he received from his relatives, Mr. Nishioka gradually recovered. While living a difficult life in his mother’s childhood home, he obtained a scholarship to continue his studies. Upon entering the workforce, he pursued a career in design and power plant work. Amid his 35 years of work, he married and had two children. He has suffered from various illnesses such as acute pancreatitis, liver damage, inflammation of the gallbladder, and intestinal obstruction, all for which he has been in and out of the hospital repeatedly for surgeries. He has also produced a kamishibai story titled, “A Thirteen-year-old Boy’s A-Bomb Experience.” From 2019, Mr. Nishioka’s story, along with the clothes he was wearing at the time of the bombing, has been displayed in the newly renovated East Wing of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Although he lives happily, surrounded by his two sons, their wives and his five grandchildren, he has never forgotten his friends and the citizens of Hiroshima who came to such a cruel end at the hands of the atomic bombing. He continues his activities to pass on his experiences of the war and the atomic bombing to the next generation.

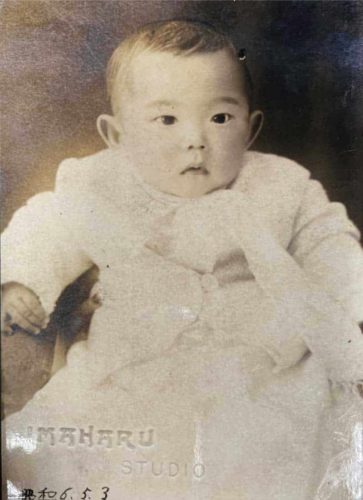

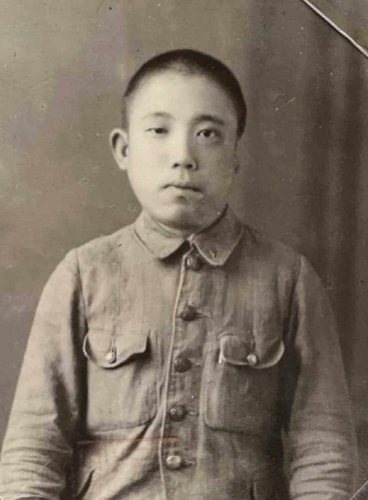

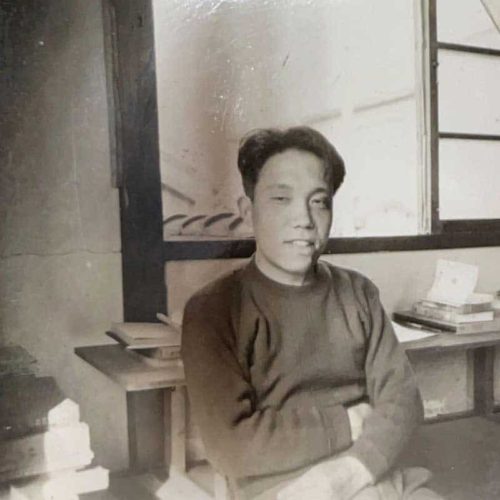

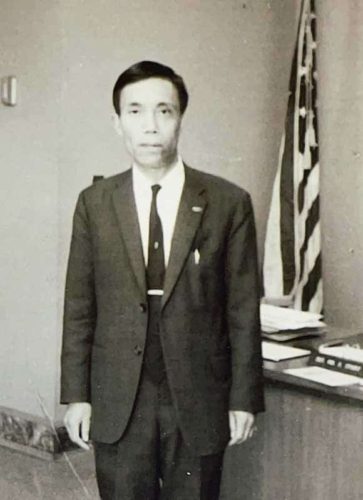

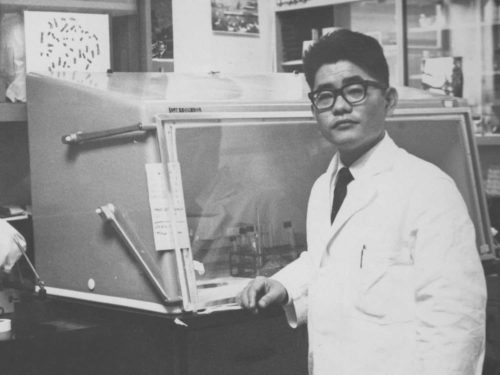

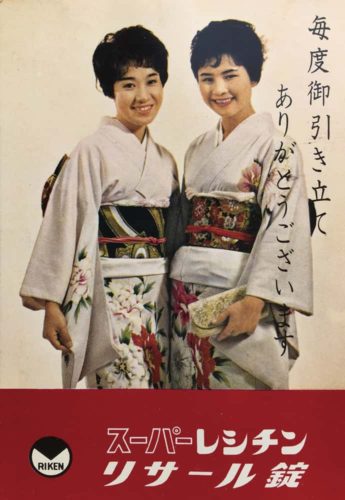

A single memory

Taken around February 1946. This picture was taken at Arakawa Photo Studio, which was established in the black market out the front of Hiroshima Station after the war. At the time, photography was a luxury, so “even a small picture made me happy,” Mr. Nshioka said.

A streak of vapor trail

from an airplane

in a blue sky…

Would you think it was beautiful?

Even now,

when I remember the B-29,

I am still scared.

On April 8, 1945, Mr. Nishioka entered Hiroshima Prefectural Technical School. After the anxious but hopeful entrance ceremony, only the new students attended classes. All the upperclassmen had already been mobilized and went off to their work in munitions factories. Eventually, the first-year students were also mobilized and went off to work too. They worked jobs such as cultivating potato fields, transporting sand and soil for air raid shelters, and pulling down buildings to create firebreaks. Children as young as 12 and 13 were engaged in hard labour, fighting against heat and hunger, but still believing that Japan would win the war.

On August 6, Mr. Nishioka was not feeling well, so he gave up on the idea of going to work pulling down buildings and instead headed to his school for other work. It was 8:15 a.m. The site where his classmates were working was 600 metres from the hypocentre. All were killed by a single atomic bomb blast that left them in unimaginable states. Mr. Nishioka survived the bombing because, by pure chance, he did not go to do his usual work that day. In his heart, he still carries with him a sense of guilt at being the only one who survived, as well the image of his classmates, who died an untimely death with no one to care for them.

A streak of vapor trail

from an airplane

in a blue sky…

Would you think it was beautiful?

Even now,

when I remember the B-29,

I am still scared.

On April 8, 1945, Mr. Nishioka entered Hiroshima Prefectural Technical School. After the anxious but hopeful entrance ceremony, only the new students attended classes. All the upperclassmen had already been mobilized and went off to their work in munitions factories. Eventually, the first-year students were also mobilized and went off to work too. They worked jobs such as cultivating potato fields, transporting sand and soil for air raid shelters, and pulling down buildings to create firebreaks. Children as young as 12 and 13 were engaged in hard labour, fighting against heat and hunger, but still believing that Japan would win the war.

On August 6, Mr. Nishioka was not feeling well, so he gave up on the idea of going to work pulling down buildings and instead headed to his school for other work. It was 8:15 a.m. The site where his classmates were working was 600 metres from the hypocentre. All were killed by a single atomic bomb blast that left them in unimaginable states. Mr. Nishioka survived the bombing because, by pure chance, he did not go to do his usual work that day. In his heart, he still carries with him a sense of guilt at being the only one who survived, as well the image of his classmates, who died an untimely death with no one to care for them.

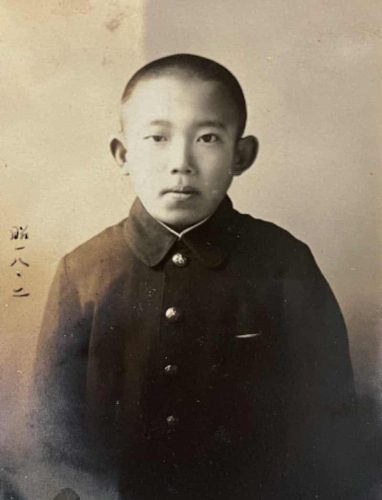

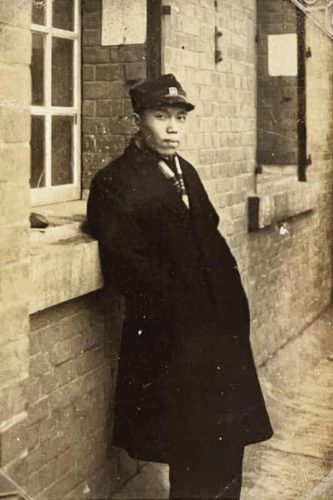

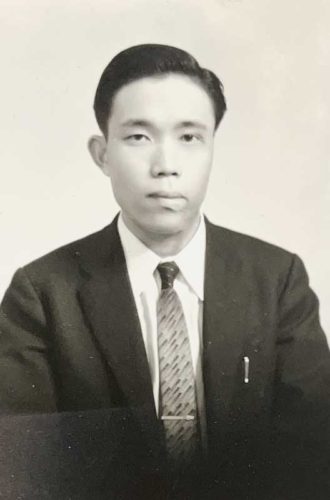

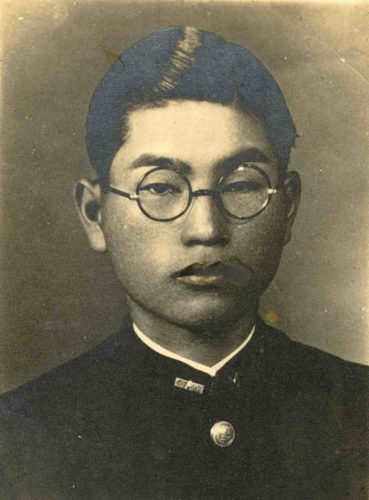

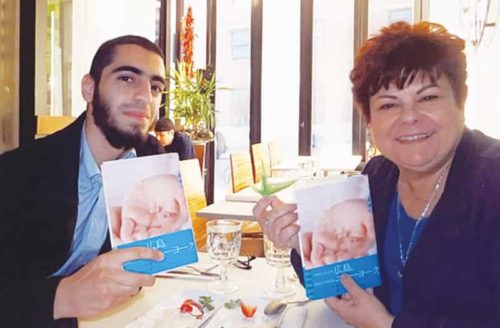

Remembering my best friend, Izuo Ito

My junior high school classmate, Izuo Ito.

Courtesy of Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims.

In December 1945, four months after the atomic bombing, Mr. Nishioka had recovered enough to walk. He visited the site where his classmates had all died. He called out his friend’s name, “Ito! Ito!” but there was no reply. Izuo Ito had been very skilled at the harmonica and was proud of his father, a lighthouse keeper. Four months after entering middle school, his best friend, with whom he’d played together every day, became a victim of the atomic bomb. He died without ever seeing his family again.

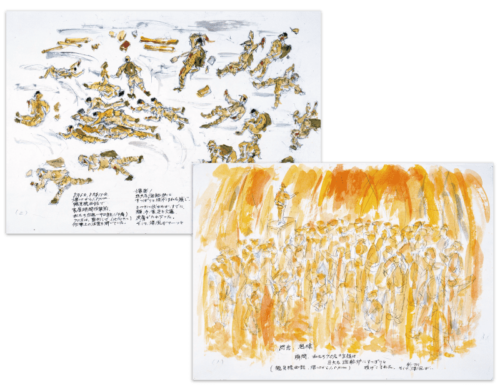

My granddaughter painted the devastation of the A-bomb

Corpses bobbing amongst the ships in the harbour, 2010.

Based on the testimony of Sadae Kasaoka, A-Bomb survivor

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum (Collection)

In 2010, Mr. Nishioka’s granddaughter, Yuka, was among a group of students of the Creative Expression Course at Hiroshima Municipal Motomachi Senior High School, who interviewed hibakusha about their experiences and the horrors of the A-bomb and painted pictures of them. Yuka said that she tried to capture the hibakusha’s memories of their painful past with a sense of duty to “prevent such a tragedy from happening again.”

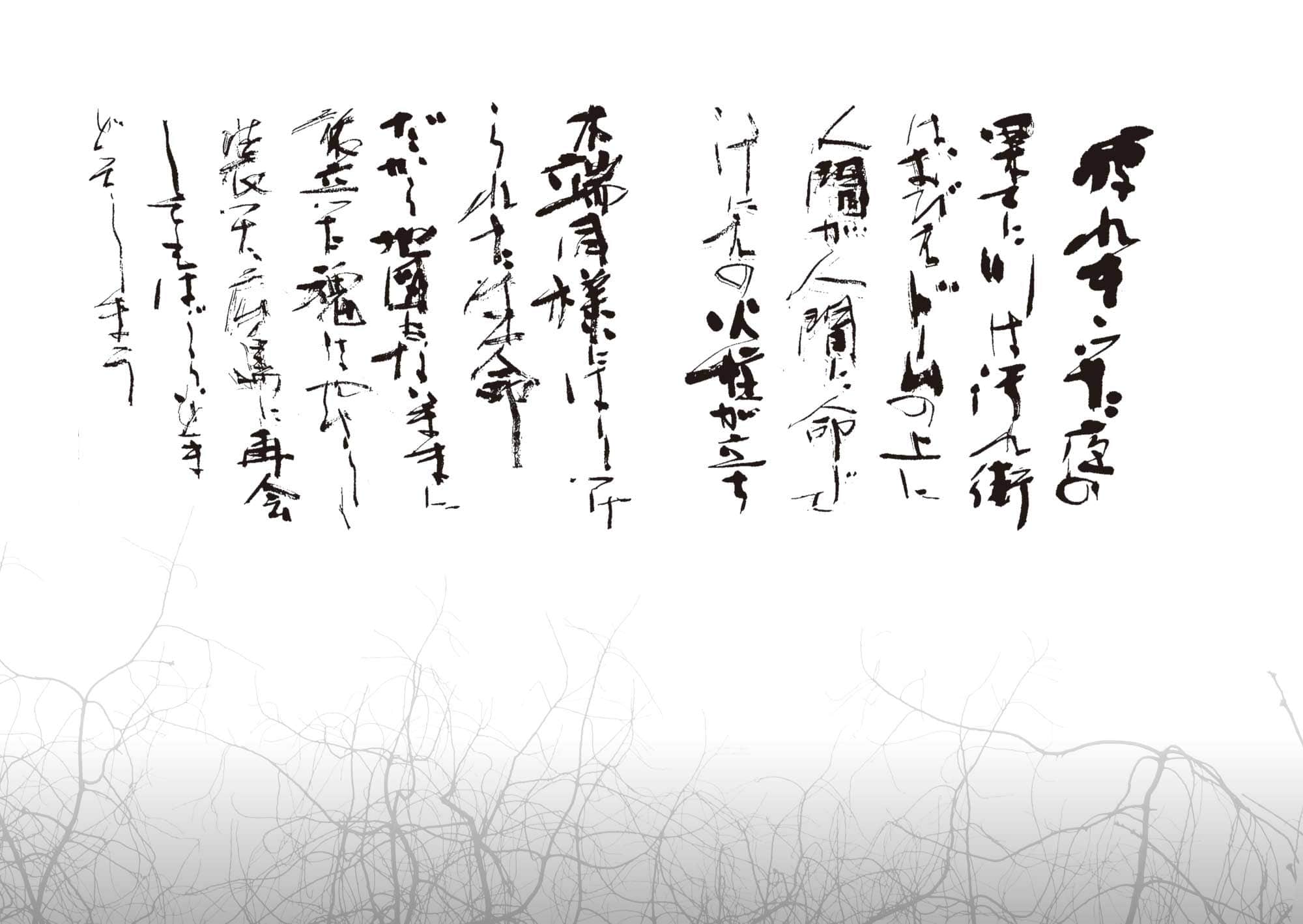

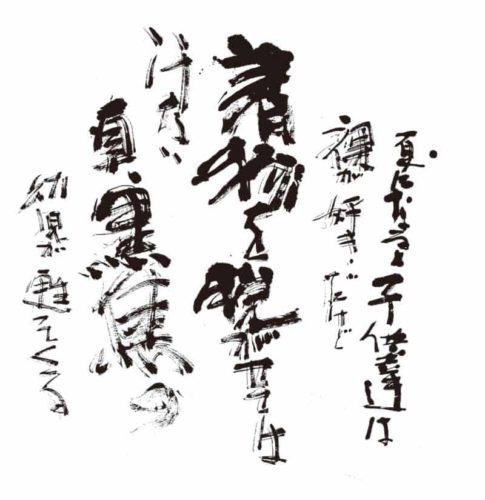

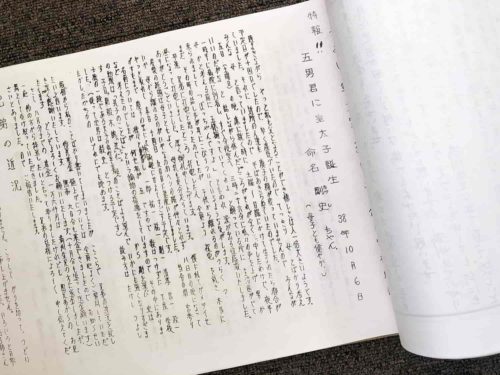

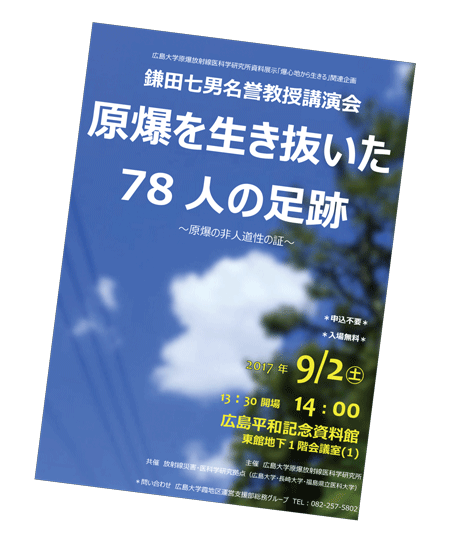

Preserving war experiences with a kamishibai

Memories of the war and the atomic bombing are painful to recall. In order to pass on those memories that he had sealed inside himself to a generation that has never known war, Mr. Nishioka has written them down. He created a kamishibai, a kind of picture theatre show, called “A Thirteen-year-old Boy’s A-bomb Experience” and which is now part of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum’s collection.

An air-raid shelter dug into the mountains near Yaga Sation on the Geibi Line railway.

Mr. Nishioka and other schoolchildren worked in pairs to transport soil and sand in woven baskets.

An air-raid shelter dug into the mountains near Yaga Sation on the Geibi Line railway. Mr. Nishioka and other schoolchildren worked in pairs to transport soil and sand in woven baskets.

They ate every single grain of rice in their lunches, which had soured in the heat.

They worked so hard at demolishing buildings that their faces were covered with black streaks of sweat and dust.

They ate every single grain of rice in their lunches, which had soured in the heat. They worked so hard at demolishing buildings that their faces were covered with black streaks of sweat and dust.

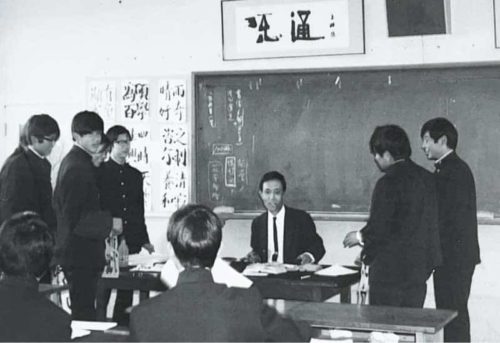

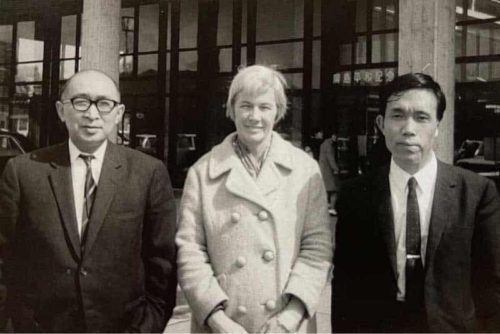

Discovering the power of the paintbrush at Auschwitz

Between 1967 and 1969, Mr. Nishioka made three long trips to Poland. Among the unforgettable encounters he had and the memories that he made, there is one thing that still remains with him to this day. It is a painting he saw when he visited Auschwitz.

“I understood instantly what had happened there,” Mr. Nishioka said. “I realised then that paintings transcend words.” This was the begging of his efforts to express his A-bomb experience through art. With the simplistic touch that is distinctive of Mr. Nishioka’s style, his paintings convey his detailed memories of the atomic bombing and the realities of what happened.

I have needed an ambulance four times and been in and out of the hospital for surgeries.

Acute pancreatitis, liver damage, inflammation of the gallbladder, intestinal obstruction.

There will be more to come.

The doctor said,

“I don’t exactly know if it’s related to the atomic bomb,

But for some reason, hibakusha tend to suffer from internal diseases like this.”

One person said,

“Hibakusha don’t have to pay for medical treatment, so they go straight to hospital.”

My cousin used to receive a health care allowance* from the government,

But his neighbour criticised him, calling him a “tax cheat”

So, he cancelled the payments.

Hibakusha did not choose to be exposed to the atomic bombings.

The atomic bomb exploded just as a young Mr. Nishioka passed through the school gate and bowed in reverence to the portrait of the emperor.* “It’s hot! It’s hot!” he cried as he instinctively came to a stop and cowered. Then a blast came and blew him away. As he lay on his stomach on the ground, covering his eyes and ears, things clattered down around him, and roof tiles fell like rain. His legs were caught under a beam-like object, and he was unable to move. He was lucky to be rescued, but his face and hands rapidly blistered, and his left leg was stained red with blood. The school was located in Hiroshima City’s Senda-machi, about 2 km from the hypocentre. The atomic bomb not only damaged the surface of Mr. Nishioka’s body but is also affecting him internally as well.

I have needed an ambulance four times and been in and out of the hospital for surgeries.

Acute pancreatitis, liver damage, inflammation of the gallbladder, intestinal obstruction.

There will be more to come.

The doctor said,

“I don’t exactly know if it’s related to the atomic bomb,

But for some reason, hibakusha tend to suffer from internal diseases like this.”

One person said,

“Hibakusha don’t have to pay for medical treatment, so they go straight to hospital.”

My cousin used to receive a health care allowance* from the government,

But his neighbour criticised him, calling him a “tax cheat”

So, he cancelled the payments.

Hibakusha did not choose to be exposed to the atomic bombings.

The atomic bomb exploded just as a young Mr. Nishioka passed through the school gate and bowed in reverence to the portrait of the emperor.* “It’s hot! It’s hot!” he cried as he instinctively came to a stop and cowered. Then a blast came and blew him away. As he lay on his stomach on the ground, covering his eyes and ears, things clattered down around him, and roof tiles fell like rain. His legs were caught under a beam-like object, and he was unable to move. He was lucky to be rescued, but his face and hands rapidly blistered, and his left leg was stained red with blood. The school was located in Hiroshima City’s Senda-machi, about 2 km from the hypocentre. The atomic bomb not only damaged the surface of Mr. Nishioka’s body but is also affecting him internally as well.

Nuclear power and atomic bombs.

Their origins are the same.

As someone who experienced Hiroshima

and was exposed to the A-bomb,

I was unaware.

Until that day.

March 11, 2011.

Decades ago, while working at a power plant, Mr. Nishioka attended a lecture on nuclear power generation in Hiroshima city. The lecture taught that “nuclear power is safe and secure, extremely inexpensive, and absolutely necessary for the future economic development of Japan.” When the lecture was over, the audience gave a long, standing ovation.

On March 11, 2011, the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred. When the incident at the Fukushima Nuclear Powerplant happened, Mr. Nishioka recalled that lecture. “At the time, everyone was convinced that nuclear power was wonderful,” he said. “Why didn’t anyone realise it’s true horror? Now we understand that ‘nuclear power’ and ‘nuclear bombs’ come from the same source.”

Nuclear power and atomic bombs.

Their origins are the same.

As someone who experienced Hiroshima

and was exposed to the A-bomb,

I was unaware.

Until that day.

March 11, 2011.

Decades ago, while working at a power plant, Mr. Nishioka attended a lecture on nuclear power generation in Hiroshima city. The lecture taught that “nuclear power is safe and secure, extremely inexpensive, and absolutely necessary for the future economic development of Japan.” When the lecture was over, the audience gave a long, standing ovation.

On March 11, 2011, the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred. When the incident at the Fukushima Nuclear Powerplant happened, Mr. Nishioka recalled that lecture. “At the time, everyone was convinced that nuclear power was wonderful,” he said. “Why didn’t anyone realise it’s true horror? Now we understand that ‘nuclear power’ and ‘nuclear bombs’ come from the same source.”

Edited and produced by ANT-Hiroshima

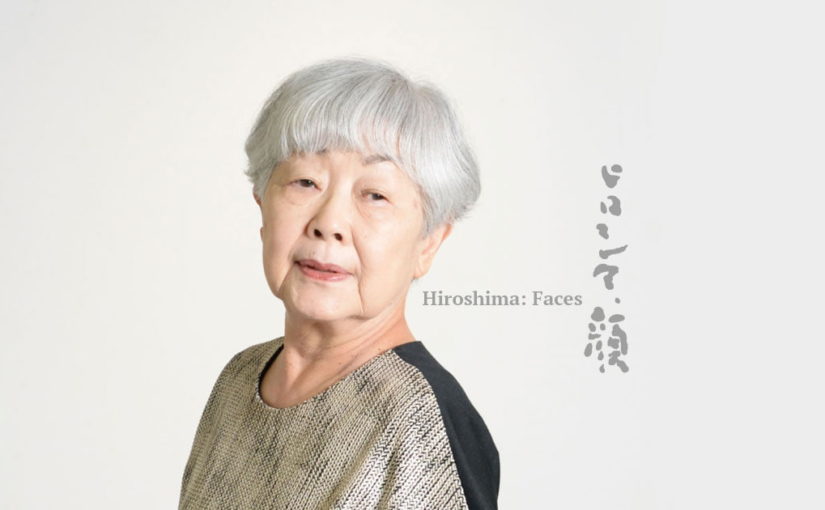

Photography by Mari Ishiko

Text by Mika Goto

Translation by Eliza Nicoll

Translation edited by Annelise Giseburt