When I got married and was blessed with my first child, I was astonished.

I was astonished at the daughter’s vitality,

desperately clinging to her mother’s breast,

even though her eyes were yet to open.

As I gazed at my sleeping daughter,

suddenly, the figure of a burnt child I had seen in the ruins floated before my eyes.

At that moment, a strong emotion sprang up in my heart.

No child should experience an atomic bombing again.

I must share my stories.

When I got married and was blessed with my first child, I was astonished.

I was astonished at the daughter’s vitality,

desperately clinging to her mother’s breast,

even though her eyes were yet to open.

As I gazed at my sleeping daughter,

suddenly, the figure of a burnt child I had seen in the ruins floated before my eyes.

At that moment, a strong emotion sprang up in my heart.

No child should experience an atomic bombing again.

I must share my stories.

-

Profile

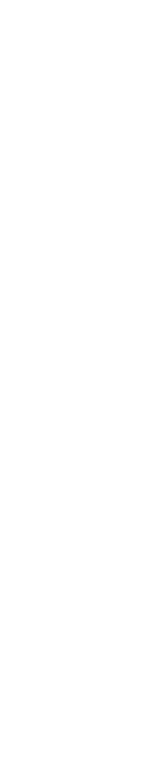

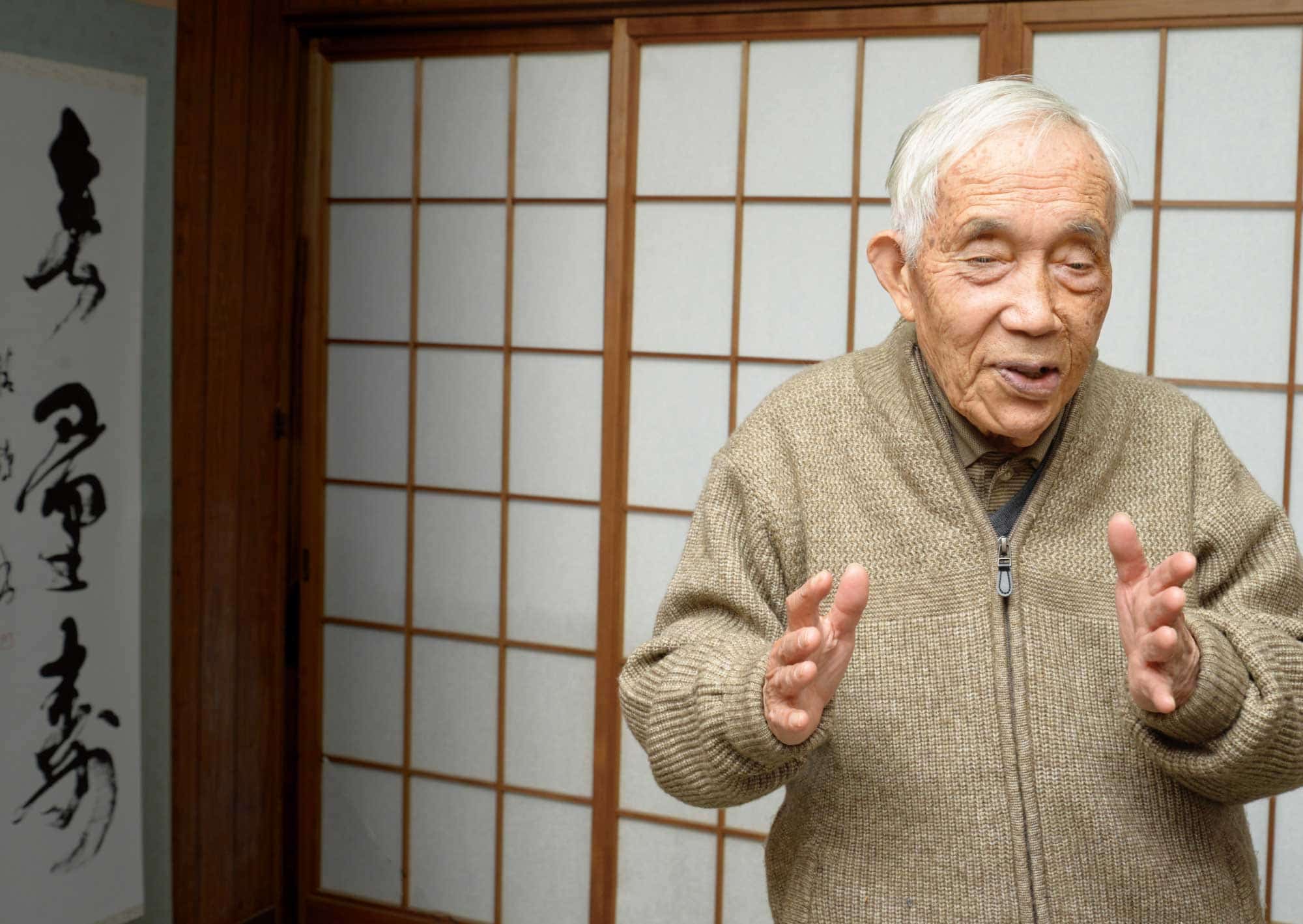

Hiromu Morishita

Hiromu Morishita

Hiromu was born in Nakano-mura, Toyota-gun, Hiroshima Prefecture, on October 26, 1930. He had a family of seven, living with his parents, grandparents, and two younger sisters — younger than him by two years and seven years. At the age of four, his father, a primary school teacher, was transferred to Hiroshima City Oshiba Normal Primary School, and his family moved to Nishi-Hakushima-cho, Hiroshima City. Following the Showa Financial Crisis, Japan entered the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) and the Pacific War (1941-1945). Hiromu grew up in an increasingly militaristic atmosphere. He graduated from an elementary school, Hakushima Kokumin School, and entered Kyusei-Hiroshima-Itchu (now Hiroshima Kokutaiji High School). Instead of studying, he worked in fields and was mobilized for local manufacturer Toyo Kogyo (now Mazda Motor Corporation) and an aviation service in Hiroshima.

On the day of the atomic bombing, August 6, 1945, Hiromu was in his third year of junior high school. He was suddenly struck by a flash of light while working on building demolition, 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. His face and hands were instantly burned severely. His mother was trapped under a collapsed building at their home in Nishi-Hakushima-cho and burned to death in the ensuing fire. His father was exposed to the bomb while deployed by a Mitsubishi Heavy Industries plant for demolition work at a temple in Kusatsu; the older of his younger sisters was exposed to the bomb at a shoe factory in Misasa but survived; the younger of the two sisters had been evacuated to Iimuro — a rural part of Hiroshima — and was safe.

Before the end of the day, Hiromu managed to reach an acquaintance’s home in Kawauchi-mura (current Asa-Minami-ku). He spent approximately two months recovering from his burns. In October, he moved to his uncle’s house in Mibu-cho (now Kitahiroshima-cho, Yamagata-gun), where his grandmother had evacuated. In January 1946, he moved to a dormitory in Gion, where his father worked. In the summer, he underwent two surgeries to treat the keloids scars on his face and neck.

The grief of losing his mother during his adolescence led Hiromu to develop his internal world, pursuing such ideals as kindness and Romanticism. In 1948, he entered Hiroshima Higher Normal School; the following year, due to the education system reform, he entered the Department of Japanese Literature in the Faculty of Letters of Hiroshima University. During his years at Hiroshima University, he severely suffered from tuberculosis and was often forced to take leaves of absence to recuperate. However, he distracted himself from his illness by writing poetry and novels.

In the spring of 1955, he began teaching Japanese literature and calligraphy at Oshita-Gakuen Gion High School. Since August 6, 1945, he could not accept his identity as one suffering from keloids due to the atomic bombing; even after becoming a high school calligraphy teacher, he never spoke about his experience of the atomic bombing. However, a turning point came when Hiromu was blessed with a daughter two years after his marriage in 1961. He sincerely felt the overwhelming vitality of life when he saw his first daughter breastfeeding; he began to talk about his experience of the atomic bombing, believing that “never again should children be sacrificed.”

In 1964, Hiromu participated for the first time in the second World Peace Pilgrimage organized by Barbara Reynolds (who later founded the World Friendship Center, a peace organization; Reynolds died in 1990), touring Europe, the United States, and the then Soviet Union to appeal for nuclear abolition. In the U.S., his group met with former President Truman, the one who decided to drop the atomic bombs. After returning to Japan, Hiromu continued to conduct surveys about atomic bomb awareness for high school students, helped found the Atomic Bombed Teachers Association, and served as the WFC President for many years until 2012.

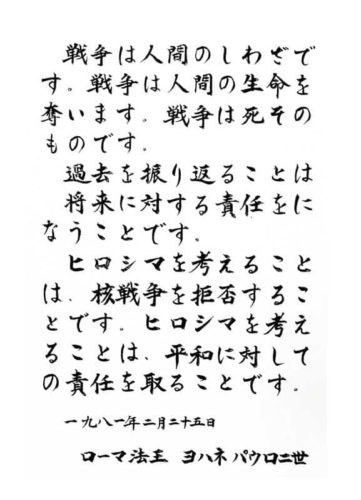

As a calligrapher, Hiromu wrote the inscription for the Pope’s appeal for peace when he visited Hiroshima in 1981. The inscription that begins “War is the work of man” still stands at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, sending a strong message to a world shaken by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. After retiring from Hatsukaichi High School in 1990, where he had worked for 30 years, he taught calligraphy at Shimane University and Hiroshima Bunkyo Women’s University (now Hiroshima Bunkyo University). Now in his 90s, Hiromu has never stopped striding towards peace.

On that day, Hiromu’s world turned upside down

▲November 3, 1936, a family picture from when Hiromu lived in Hakushima. Hiromu was around six years old (center).

August 6, 1945. Hiromu, who was 14 years old and in his third year of junior high school, was not feeling well that day and was told by his doctor to take a day off. However, his father told him to attend for the day and tell them that he would take the next day off, so he reluctantly left his home.

While working to demolish buildings at the foot of Tsurumi Bridge, about 1.5 km from the hypocenter, Hiromu was suddenly hit by a flash of light. He reflects, “It was so hot, like being thrown into a massive furnace.”

Hiromu’s face and neck were burned severely, and his friends nearby also had peeling skin on their faces. While escaping, he saw lines of soldiers with their hands stretched out like ghosts, and the charred bodies of dead infants. His mother, who had seen him off from the doorstep earlier that day, had passed away.

“Seeing the shattered bones of my mother that my father collected

My father and grandmother burst into tears

Exhausted with pain, I can’t even cry”

From the anthology “Faces of Hiroshima”

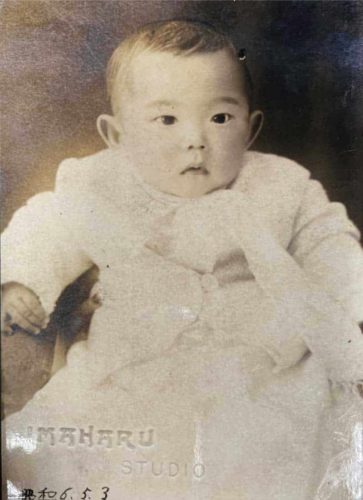

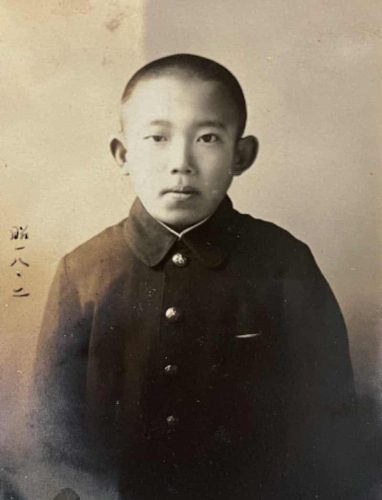

▲A photo captioned “May 3, Showa 6 (1931)”. Hiromu was six months old.

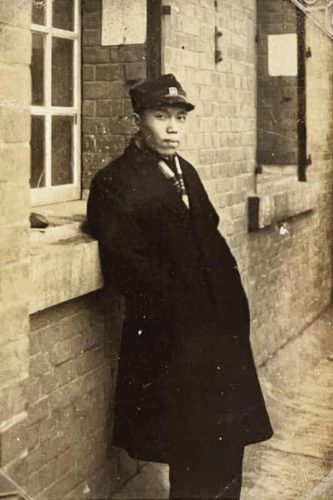

The caption reads “February, Showa 18 (1943).” Hiromu was 13 years old, in his first year of junior high school.▼

Mother passed away, Hiromu was left with keloids: Mental and physical wounds

Hiromu’s sense of grief over the loss of his mother escalated as he went through adolescence. His mother, who had so kindly seen him off at the door, reduced to nothing but white bones a few days later was too cruel and difficult for a 14-year-old boy to accept. “I would feel like my mother was going to show up somehow. My desire for kindness, a presence that would watch over me, grew stronger,” he said. The atomic bomb destroyed the city of Hiroshima. As if to erase the feeling of emptiness that “everything that has physical form crumbles and breaks down,” Hiromu sought something eternal, something that will never perish, something Romantic.

On the other hand, the keloids left on his face and neck became a “visible trauma” that tormented Hiromu for a long time. He felt the pain of not being able to escape the gazes of those around him. He hated looking in the mirror. He could not accept himself.

“The dome, it is my keloids. Fetters that I cannot escape. Though I want to destroy it, I do not because if I do, the world will collapse.”

In his collection of poems, “Faces of Hiroshima,” Hiromu expresses his internal conflict by comparing the Atomic Bomb Dome to his keloids.

▲Hiromu after the atomic bombing.

▲In 1946, at the site of Hiroshima Army Hospital Eba Branch. Hiromu met with his schoolmates for the first time since the atomic bombing. “Some of my friends had died, some, like me, had lost family members, and some had suffered burns. The values of militaristic education had collapsed, and we had lost everything. We were not in the condition to be sincerely happy to see friends again. I felt like screaming out loud.”

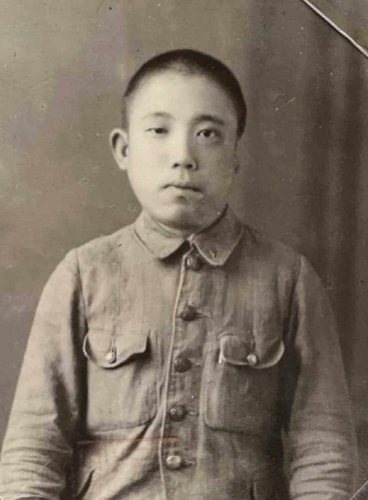

A drawing Hiromu made depicting his experience of the atomic bombing. In addition to the devastation he saw and experienced, he also depicted his friends’ experiences. The caption reads “A flash of light, a heat ray. In an instant, we 70 students were thrown into a huge furnace. And then the hot wind… (West of Tsurumi Bridge, 1.5km from the hypocenter)”

Reserved and provided by the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

▲A drawing Hiromu made depicting his experience of the atomic bombing. In addition to the devastation he saw and experienced, he also depicted his friends’ experiences. The caption reads “A flash of light, a heat ray. In an instant, we 70 students were thrown into a huge furnace. And then the hot wind… (West of Tsurumi Bridge, 1.5km from the hypocenter)”

Reserved and provided by the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

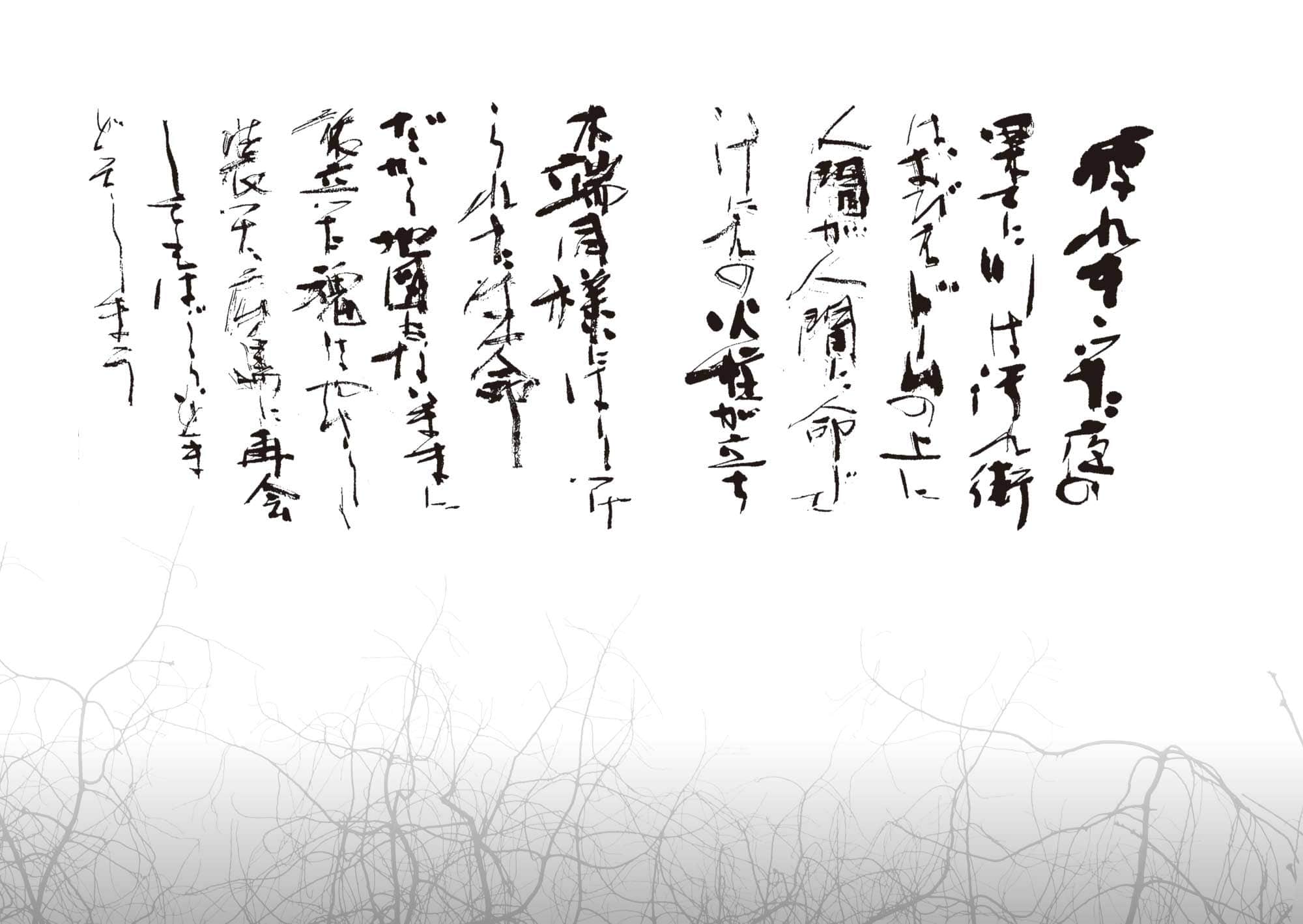

My father would often tell me the story of “Living with the acceptance of being bald.”

There was a monk who was bald since a young age.

Don’t be ashamed of your appearance,

Just be a person of pure heart.

He would comfort me with this story when I was bothered by my keloid scars.

Be a person of pure heart…

That is how I came to pursue the internal aspects of life through literature, poetry, and tanka (Japanese short poems).

My father would often tell me the story of “Living with the acceptance of being bald.”

There was a monk who was bald since a young age.

Don’t be ashamed of your appearance,

Just be a person of pure heart.

He would comfort me with this story when I was bothered by my keloid scars.

Be a person of pure heart…

That is how I came to pursue the internal aspects of life through literature, poetry, and tanka (Japanese short poems).

Seeking solace in literature: Deeply observing daily lives, refining senses

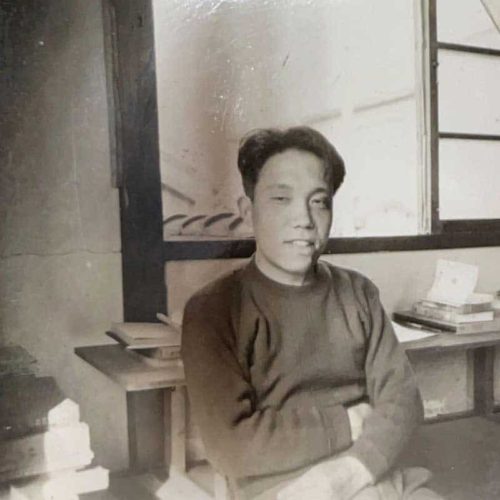

▲Hiromu when he was in Hiroshima Higher Normal School (Now Hiroshima University, Faculty of Education).

▲A former army clothing factory in Hiroshima was used as a campus building for the Hiroshima Higher Normal School for several years from 1946. This is one of the rare photographs of the former army clothing factory at the time.

Knowing his son was bothered by his keloids, Hiromu’s father kept encouraging him not to worry about his appearance, which cannot change, but to refine his mind. Hiromu is still grateful to his father for this encouragement, which he says “led me to deepen my inner quest” in later life. While he studied at Hiroshima University, Hiromu immersed himself in writing poems and novels, but it took him six years to graduate from the university as he went through treatments for tuberculosis.

A friend suggested that Hiromu write tanka poems since he would be bored in his sickbed, so he joined a tanka poetry society and devoted himself to creating tanka poems. The society was based on aestheticism, which encouraged him to find beauty in life. Measuring body temperature with a thermometer — if the mercury scale rises, the body has a fever, which is considered “bad.” Aestheticism, however, considered the movement itself “beautiful.” By observing everyday life, his sensibility was refined. Hiromu contributed to magazines, and participated in literary criticism groups; his tanka poem writing, which was merely a way to pass the time on his sickbed, eventually became his ikigai — his purpose in life — and empowered him for his later creative activities, such as poetry and calligraphy.

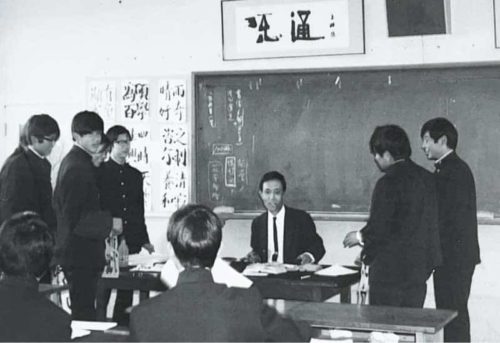

When Hiromu was about to start his teaching career, he met people who were essential in the history of hibakusha in Hiroshima, such as Mr. Ichiro Kawamoto (center, back row) and Mrs. Ikimi Kikkawa (center, front row) who inspired him. Hiromu is on the right.

▲When Hiromu was about to start his teaching career, he met people who were essential in the history of hibakusha in Hiroshima, such as Mr. Ichiro Kawamoto (center, back row) and Mrs. Ikimi Kikkawa (center, front row) who inspired him. Hiromu is on the right.

Becoming a teacher: unable to disclose that he is a hibakusha

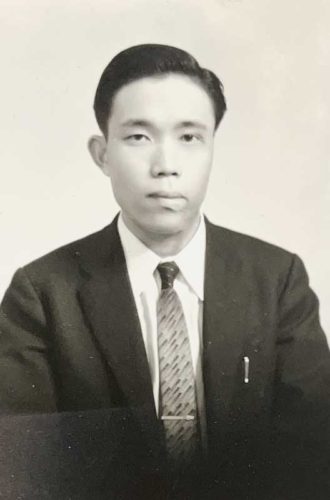

▲Taken around the time Hiromu started teaching Japanese and calligraphy at Oshita-Gakuen Gion High School. He taught only a few days per week due to the continued treatment of his tuberculosis.

◀Taken around the time Hiromu started teaching Japanese and calligraphy at Oshita-Gakuen Gion High School. He taught only a few days per week due to the continued treatment of his tuberculosis.

In 1956, more than ten years after the end of the war, an exposition on the peaceful uses of nuclear energy was held at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. As a teacher in a girls’ school, Hiromu went to the exposition on a school trip. “Tracking diseases (radioisotopes), and providing energy for airplanes and ships. The exhibit was praising the wonderful things that nuclear power can do.”

At the same time, however, memories of the atomic bombing remained in the same museum. Seeing exhibits like specimens of keloids and relics melted by the bomb’s intense heat, students whispered, “I’m scared, I’m scared,” and “I might not be able to sleep tonight.” Hiromu was enjoying his days as a teacher when he suddenly came to his senses. He thought, “What do these students think of me in the classroom? And my keloids. Ugly things are ugly, aren’t they…” He began to avoid topics related to the atomic bombing and even thought of terminating his teaching career.

Hiromu when he became a teacher. Having suffered from tuberculosis and undergone long-term medical treatment for a pneumothorax while a student at Hiroshima University, he was extremely happy to be able to leave his hospital bed and work.

▲Hiromu when he became a teacher. Having suffered from tuberculosis and undergone long-term medical treatment for a pneumothorax while a student at Hiroshima University, he was extremely happy to be able to leave his hospital bed and work.

At the limit of an exhausting night,

The river is polluted and the city terrified

At the top of the dome,

people give a command to people to offer a sacrifice,

and a fire roars

Lives crucified like tiny splinters of wood

That is why those souls that departed without a map,

when reunited with kindly disguised Hiroshima,

shyly stay where they are

An excerpt from “A Green Dome”

From a collection of poems “Faces of Hiroshima” by Hiromu Morishita

Inspired by the birth of his daughter: Hiromu shares his story for the sake of all children

▲Hiromu taught calligraphy at Hatsukaichi High School in Hatsukaichi City, Hiroshima. As a hibakusha and a teacher, he also began peace education lessons, which he devoted himself to.

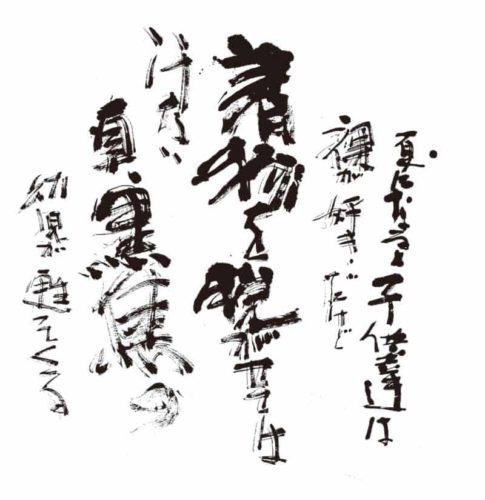

▲Hiromu’s calligraphy: “Although children like to run naked in summer, don’t let them take off their kimono — I see again the toddlers charred black.”

Hiromu had believed war would never happen again; however, the start of the Korean War in 1950 betrayed his faith. He wondered if nuclear weapons, which had had caused him so much pain, would be used again. Although anti-war activists urged him to lead protest actions because he had keloid scars, Hiromu firmly believed that keloids should not be used as a PR tactic.

After finding work as a calligraphy teacher at a prefectural high school, Hiromu was so occupied with daily tasks that he purposefully did not reflect on his past. In his 30s, he married and started a family — that’s when his thinking changed.

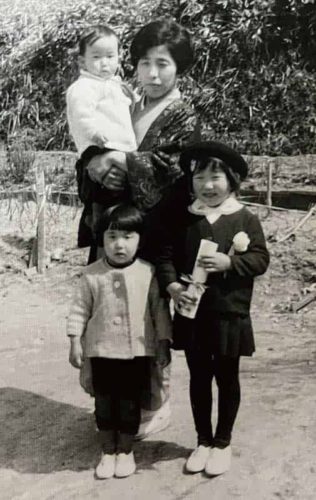

Hiromu felt a strong vitality and happiness at the sight of his daughter desperately clinging to his wife’s breast. At the same time, the sight of his daughter recalled for Hiromu the face of the charred infant he had seen in the burnt ruins after the atomic bombing.

“Such precious children must never face that cruel fate again,” Hiromu thought. Although he had avoided speaking about his experience of the atomic bombing, his daughter — her eyes not even open yet — encouraged Hiromu to begin sharing his testimony.

▲Hiromu’s wife, Hisako, and their three children.

Hiromu’s family was always his emotional rock.

▲Hiromu together with his second daughter and eldest son.

◀(Left)

Hiromu’s wife, Hisako, and their three children. Hiromu’s family was always his emotional rock.

(Right)

Hiromu together with his second daughter and eldest son.

Meeting Barbara Reynolds and beginning peace activism

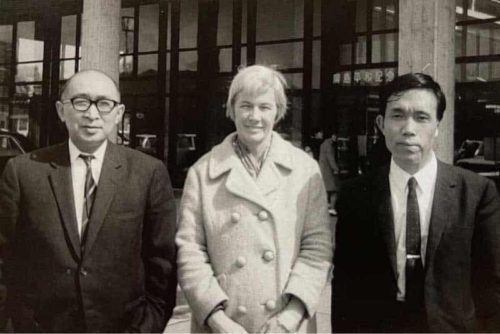

▲Hiromu (right) with Barbara Reynolds (center) and Kaoru Ogura, a Hiroshima City official who served as Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation Executive Director and Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum Director prior to his death in 1979.

▲With a host family in Illinois, United States.

▲Before the departure of the Peace Pilgrimage: Hiromu’s wife, Tsuneko (right); his father and eldest daughter (center); Tsuneko’s mother (left).

Barbara Reynolds (1915-1990) first came to Hiroshima in 1951 as the wife of a member of an Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC) staff member. She became deeply involved in peace activism after meeting hibakusha, and in 1965, she founded the peace organization World Friendship Center (WFC) in Hiroshima city. Even after returning to the U.S. in 1969, she busily continued her anti-war, anti-nuclear activities.

“She struck me as a kind woman when I first met her. But I was truly inspired when I saw the frugal life she lived, having spent her personal fortune to support her activities,” Hiromu said.

Hiromu served as WFC’s director for many years until 2012, out of respect for Barbara and as well as for Tomin Harada (1912-1999), the WFC’s first director and a surgeon who devoted himself to the treatment of hibakusha.

In the 1960s, around the time Hiromu decided to share his experience of the atomic bombing, events such as the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962) and China’s first nuclear tests (1964) heightened tensions over nuclear weapons. Amid these events, Hiromu learned that Barbara Reynolds had organized a World Peace Pilgrimage, and he participated for the first time. He traveled for 75 days with roughly a dozen hibakusha and an interpreter to eight countries, including the U.S., France, and the Soviet Union, to call for the abolition of nuclear weapons.

Although the U.S. had deprived Hiromu of his mother and made him suffer as a hibakusha, he had no hesitation in visiting the U.S. He also learned that members of American NGOs and others were supporting his pilgrimage, and he felt no hatred. Curiosity, too, encouraged him on his journey.

“Forgive me, forgive me!”

I was in the U.S. on the Peace Pilgrimage, praying at a church after a peace conference.

An elderly American man came up to me, weeping, his large body shaking.

His feelings after hearing my testimony must have been unbearable.

There are people in the U.S., too, who weep at the cruelty of the atomic bombings and wish for an end to war.

“Forgive me, forgive me!”

I was in the U.S. on the Peace Pilgrimage, praying at a church after a peace conference.

An elderly American man came up to me, weeping, his large body shaking.

His feelings after hearing my testimony must have been unbearable.

There are people in the U.S., too, who weep at the cruelty of the atomic bombings and wish for an end to war.

Meeting former President Truman

Meeting former President Truman

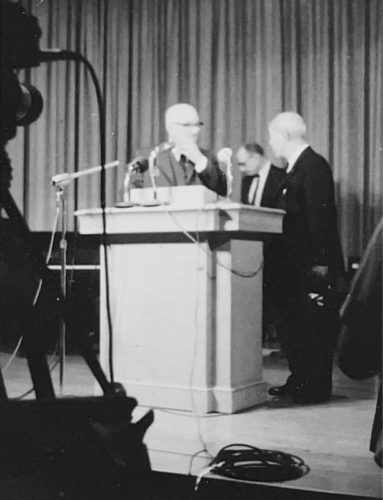

▲Former U.S. President Harry S. Truman at the Truman Library, with the stage set as if for an interview. The Japanese delegation, including Hiromu and other hibakusha, watched with bated breath.

After the meeting with former President Truman, in the midst of all the excitement, Hiromu took his pen and recorded his impressions. He keeps the precious notes still today.

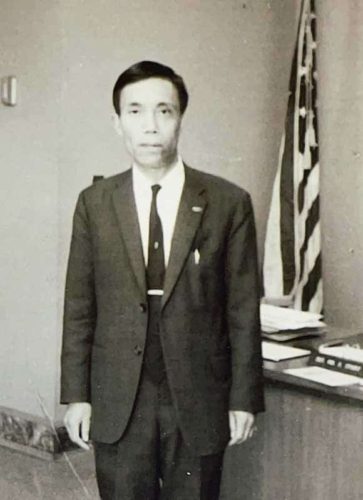

▲Hiromu after the meeting with former President Truman.

▲After the meeting with former President Truman, in the midst of all the excitement, Hiromu took his pen and recorded his impressions. He keeps the precious notes still today.

While staying in the U.S. in 1964, Barbara arranged for the Japanese delegation to meet with former U.S. President Harry S. Truman, the face of what the Japanese had referred to as “Western brutes” during World War II. Truman, the head of the Japanese delegation, and an interpreter spoke on stage, while Hiromu and the others watched from the audience.

“I don’t want that kind of thing to happen again,” Truman said, an ambiguous statement that could mean either the war or the atomic bombings. Hiromu later felt that Truman was implying that the atomic bombings were necessary to save the lives of many U.S. soldiers and end the war. The meeting lasted only three minutes. Truman closed by saying that international disputes should be resolved through the United Nations, which he had helped create.

Some said Truman should be commended for meeting with hibakusha, but from the hibakusha’s point of view, the meeting had been a letdown. Hiromu, too, expressed his disappointment in a contemporaneous memo.

“I wanted Truman to say that he was sorry for doing such a terrible thing. Did the young children in Hiroshima and Nagasaki not cross his mind when he made the decision to drop the bombs?” he recalled.

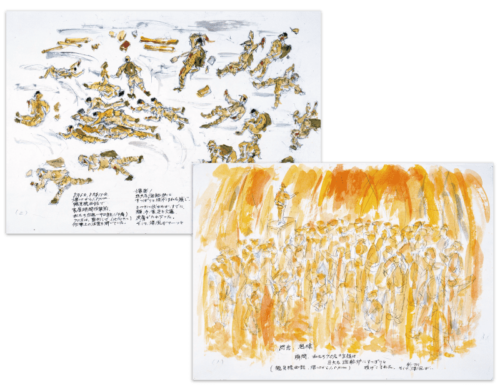

Hiromu in his 90s: Sharing his story as long as he lives

Speaking with Veterans of Foreign Wars in the U.S., Hiromu sometimes heard the same response that Truman had given: “We were in the right.” However, in other places, people understood that the atomic bombings had not hastened the end of the war. Hiromu felt it very significant that the hibakusha’s message was heeded not only in the A-bombed cities themselves but around the world, and that there were non-Japanese who sympathized with them.

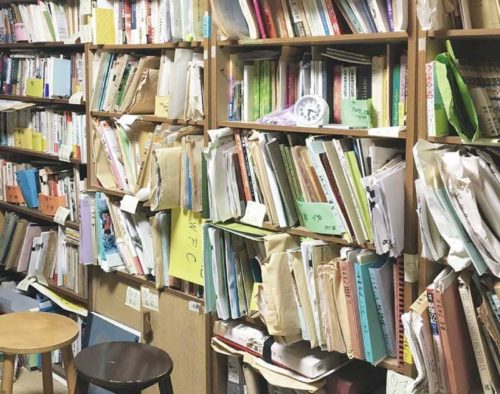

Although the COVID-19 pandemic put a damper on Hiromu’s work sharing his experience of the atomic bombing, he continued to give his testimony online. Now in his 90s, Hiromu’s physical fitness reflects his age; he has difficulty hearing and walking. However, his desire to share his story shows no sign of waning — for the sake of the children who perished in the cruel light and heat that summer; for Barbara, who devoted half her life to peace; and for today’s children, who don’t know the horrors of the atomic bombing. The tens of thousands of documents — memos, records, and clippings — kept in his home are the essence of hibakusha Hiroshi Morishita, who has wished for peace since Aug. 6, 1945.

▲One of Hiromu’s masterpieces as a calligrapher is an inscription for a stone monument, displayed at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. The words are Pope John Paul II’s call for peace from his 1981 visit to Hiroshima. “As a hibakusha, I felt his support for anti-nuclear and anti-war activities,” Hiromu said. After being asked to contribute the inscription, Hiromu made numerous versions, perfecting it with great care.

▲In his home, Hiromu keeps an overwhelming volume of valuable documents related to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, nuclear weapons, peace, calligraphy, poetry, and literature.

▼In Hiromu’s study on the second floor of his house, from which he also shares his A-bomb testimony online.

“I, too, am a hibakusha.”

These words, engraved in the monument to Barbara Reynolds that stands quietly in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park (Naka Ward, Hiroshima City), are Hiromu’s calligraphy. His pen name as a calligrapher is Seikaku Morishita. Even today, he continues to take up his brush from time to time.

“I, too, am a hibakusha.”

These words, engraved in the monument to Barbara Reynolds that stands quietly in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park (Naka Ward, Hiroshima City), are Hiromu’s calligraphy. His pen name as a calligrapher is Seikaku Morishita. Even today, he continues to take up his brush from time to time.

Edited and produced by ANT-Hiroshima

Photography by Mari Ishiko

Text by Yoshinobu Yamamoto and Mika Goto

Translation by Noa Seto and Annelise Giseburt

Translation edited by Annelise Giseburt