Through the broken ceiling

and the roof,

I saw the blue sky.

“Oh, how beautiful,” I thought.

I was six

and I knew nothing about

atomic bombs,

radiation,

and mushroom clouds.

Burned and crying,

I gazed up at the blue sky.

Through the broken ceiling

and the roof,

I saw the blue sky.

“Oh, how beautiful,” I thought.

I was six

and I knew nothing about

atomic bombs,

radiation,

and mushroom clouds.

Burned and crying,

I gazed up at the blue sky.

-

Profile

Toshiko Tanaka

Toshiko Tanaka

(former name: Katsuko Hara)

On October 18, 1938, Toshiko was born in Kako Town, Hiroshima City (today’s Nakajima Town, Naka Ward, about 1 km from the hypocenter). Her family members included her father, mother, two younger sisters — one, two years younger; the other, six years younger — and a brother born after World War II.

Her parents ran an inn for soldiers. These visitors helped take good care of her, and she grew up in good health.

After completing Mutoku Kindergarten in March 1945, Toshiko was evacuated to a relative’s house and enrolled at Yoshida Elementary School in the Takata district. Her parents, however, were worried about their little girl and brought her back home in May, then enrolled her in Nakajima Elementary School. In the summer of 1945, the Japanese military ordered her family to move out of the area. One week before the atomic bombing, they moved to Ushita, Minami Ward (today’s Ushita Waseda, Higashi Ward, about 2.3 km from the hypocenter), and she transferred to Ushita Elementary School.

On the morning on August 6, 1945, as six-year-old Toshiko was waiting for her friend under a cherry tree to go to school together, the atomic bomb exploded in the sky above the city. Though burned by the blast, she managed to make it home. That night, she had a high fever and lost consciousness. Later, at the age of 12, she was told by a doctor that her white blood cell count was abnormal.

She also developed canker sores, one after another. Her throat became swollen, and she could barely swallow any food. She suffered from extreme fatigue and feared that she would die.

In her second year at Noboricho Junior High School, her teacher urged her to run for student council president, but she had little time outside of helping her mother with work mending clothes and delivering these clothes to customers on her father’s bicycle. Despite her busy days, she wanted a way to express herself, so she became the president of the school’s newspaper club. She then devoted herself to the club’s activities. After graduating from junior high, she decided to pursue illustration and design, things she had been interested in since she was little. She took evening classes at Kokutaiji High School for four years, while also working, and saved money to go to Bunka Fashion College in Tokyo to study design and become a designer.

After earning her college degree, she returned to Hiroshima. In 1964, at the age of 25, she got married and had two children. At the suggestion of her mother-in-law, she changed her name from Katsuko to Toshiko and started taking enameling lessons. Enameling wasn’t something she had considered doing until then.

She studied under the enamelist Keiichi Saito for six years and immersed herself in the world of enameling. Her works began to gain recognition from the Japan Fine Arts Exhibition and the Japan Contemporary Arts and Crafts Exhibition, and she became a regular member of each. Keeping her ambitions high, she also studied at Tokyo University of the Arts and at an art school in New York for a short time.

In 1981, one of her pieces was presented to Pope John Paul II by the mayor of the City of Hiroshima.

During the period from 2007 to 2017, she traveled around the world on Peace Boat four times, sharing her experiences of the atomic bombing.

In 2016, she remodeled part of her house and established the “Peace Exchange Space.”

Now a freelance artist, the theme of her enamel works is “the connection between human beings and nature in the universe.” As an A-bomb survivor, she has been dedicated to relating her account of the atomic bombing. She has been involved in the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), Hibakusha Stories (a New York-based NPO working to pass on the legacy of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to the next generation), and the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo).

Childhood

This family photo was taken before her father (left) went off to war. Toshiko (held by her mother in the center) was the family’s first daughter and was raised with love.

Toshiko at nine months old

Toshiko at two years old

Toshiko’s parents ran an inn for soldiers in Kako Town, Hiroshima City (today’s Nakajima Town, Naka Ward, Hiroshima City). Soldiers drafted from all over Japan stayed at the inn before departing for the war from Ujina Port. “Their family members were back at home,” she said, “and they took really good care of me, like I was their child or a member of their family.” Toshiko was a curious child, scolded for watching martial arts practice in the neighborhood late at night and hunting for clams by the river. Though life during the war was hard, she sought enjoyment in small, everyday things. However, in the summer of 1945, the Japanese military decided to demolish the area where Toshiko’s family lived, and they were ordered to move. Just one week before the atomic bombing, the family moved to Ushita, Minami Ward (today’s Ushita, Higashi Ward). What if they had continued living in the area where they had been, which is within a 1 km-radius of the hypocenter? Their destiny was determined by chance.

Six-year-old Toshiko in the summer, after surviving the atomic bomb

On the morning on August 6, 1945, Toshiko was waiting for her friend under a cherry tree so they could walk to school together. Then someone shouted ”Enemy plane!” and she looked up at the sky. At that instant, there was a flash of white light. The atomic bomb was dropped at 8:15 a.m. When the bomb exploded, Toshiko immediately tried to protect her face, but her head, her neck, and her right arm still suffered burns.

She managed to walk home, yet she had no idea what had just happened. When Toshiko’s mother saw her — with her hair burnt and frizzy, her face and arm charred black, and her clothes in tatters — she couldn’t even recognize her own daughter. Toshiko was crying from the pain and fear she felt. At one point she looked up and saw the blue sky through the broken roof. “It was so beautiful,” she said. “It made me feel that this wasn’t the end and there would still be a tomorrow.” She still clearly remembers that blue sky.

The blisters from her burns were very painful. That night, she had a high fever and lost consciousness. A few days later, when she came to, the air was filled with the smell of dead bodies being cremated.

Graduation photo at Mutoku Kindergarten, taken in March 1945. The school was located where Peace Memorial Museum now stands. The atomic bomb was dropped five months after this photo was taken. Toshiko’s heart still aches for the friends who may have lost their lives in the explosion.

Toshiko at the age of eight. The radiation released by the atomic bomb threatened the health of her small body. When she was 12, she suffered from extreme fatigue each day and was told by her doctor that her white blood cell count was abnormal. “My friends died one after another, even though they had suffered no burns,” she said. “Back then it was believed that people within a 2 km-radius of the hypocenter would be affected by the radiation. I was in Ushita, which was 2.3 km away, a difference of 300 meters. People would say that the bomb had nothing to do with my symptoms.”

I never imagined that I would start enameling.

Sometimes in life, things unfold in an unexpected way.

What is important is

working hard on what is in front of you

and continuing to ponder

your dreams, goals, and mission.

You will eventually arrive at where you want to go

even if the form of that destination is different.

I believe that.

I never imagined that I would start enameling.

Sometimes in life, things unfold in an unexpected way.

What is important is

working hard on what is in front of you

and continuing to ponder

your dreams, goals, and mission.

You will eventually arrive at where you want to go

even if the form of that destination is different.

I believe that.

Younger years, studied cutting-edge design in Tokyo

Toshiko in her third year of junior high school

A completion ceremony was held every year at the end of a term. Junko Koshino, Kenzo Takada, and Issey Miyake were students at the same school.

Toshiko (left) took a year off from her studies at Bunka Fashion College to stay in Taiwan as a campaign model of a pharmaceutical company for four months and travel around the region. After the campaign concluded, she visited Hong Kong, Vietnam, Thailand, and Singapore. Although, at the time, it was difficult for average people to go abroad, she traveled around Asia by herself with her curious, active nature.

Life after the war was never easy. She took evening classes at a high school for four years while working, and saved money to go to Bunka Fashion College in Tokyo, where she studied design. She was asked by a renowned designer to become an apprentice, but she had nearly run out of her savings and decided to go back to Hiroshima. In 1964, at the age of 25, she agreed to an arranged marriage in Hiroshima.

She had two children and became a stay-at-home mother. Parenting kept her busy. Then, one day, her mother-in-law suggested that she take enameling lessons. At first, she wasn’t serious about this interest, but meeting the enamelist Keiichi Sato showed her the possibilities of enameling. She then immersed herself in the world of enameling and creating works of art. Keiichi Saito, Toshiko’s teacher, valued traditional crafts and viewed her as too audacious in her works. Still, she came to be recognized in the field and received a series of awards.

Decades later, a large package was delivered to her. “Inside were Mr. Saito’s tools and a letter,” she said. “He had written to me, ‘You were my finest student.’ He praised me as an enamelist. That was a few months before he died.”

Returning home, becoming immersed in the world of enameling

Toshiko began to stand out as an enamelist. Her works were accepted annually for the Japan Contemporary Arts and Crafts Exhibition starting in 1978 and first accepted for the Japan Fine Arts Exhibition in 1979, for a total of 16 acceptances. In 1981, when Pope John Paul II was making his first visit to Hiroshima, one of her works was presented to him by the mayor of Hiroshima. In the same year, she received a request from Kazu Sueishi from the American Society of Hiroshima Nagasaki A-Bomb Survivors. “We want to invite doctors from Hiroshima so that A-bomb survivors living in the U.S. can obtain a survivor’s health card, but we don’t have enough funds. May we ask for your help?”

Toshiko, with the help of the director of the City of Hiroshima’s division for international exchange, decided to hold a Japan-U.S. exchange enamel exhibition at the Japanese American Cultural & Community Center located in Los Angeles. Representing enamelists, she called for works from all over Japan. She also exhibited her own works. The event was held for two weeks, and she donated all the proceeds from sales to the American Society of Hiroshima Nagasaki A-Bomb Survivors. Her activities as an enamelist naturally led to her efforts to promote peace.

Keiichi Saito (second from the right), an enamelist and Toshiko’s teacher

Toshiko (third from the right) at the Japan-U.S. Exchange Enamel Exhibition held in the U.S. in 1981. “We brought 200 copies of the English version of ‘Barefoot Gen’ (a manga series based on the experiences of Keiji Nakazawa, an A-bomb survivor) and 400 other A-bomb-related books and donated them to the American Society of Hiroshima Nagasaki A-Bomb Survivors, and then the members of the organization gave the books to libraries.”

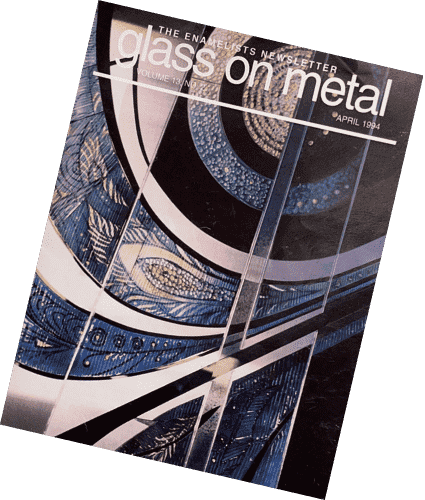

Toshiko was featured in the April 1994 issue of “Glass on Metal,” a U.S. magazine dedicated to enameling.

What is enameling?

Enameling is a process by which powdered glass is fused onto metal. While it is generally applied to accessories, Toshiko invented her own style of combining enameling and stainless steel into large mural works. Ever since then, she has introduced novel enamel works to the world.

On the boundless ocean

I felt that the world is interconnected.

Seen from the universe, the earth looks like a small boat.

We all are the crew of one boat.

Conflicts definitely impact us all.

That is why

we must not produce,

possess,

or use nuclear weapons.

We must eliminate them.

As an A-bomb survivor, that is my sincere wish.

On the boundless ocean

I felt that the world is interconnected.

Seen from the universe, the earth looks like a small boat.

We all are the crew of one boat.

Conflicts definitely impact us all.

That is why

we must not produce,

possess,

or use nuclear weapons.

We must eliminate them.

As an A-bomb survivor, that is my sincere wish.

Took Peace Boat voyages around the world, started telling her story at 70

Her efforts to speak out began with a Peace Boat voyage and an encounter in Venezuela. Once she opened up, she could not help but share what had been in her mind for a long time.

In 2005, Toshiko lost her husband, who had been her strongest supporter, and this left her with a deep sense of loss. One day in 2007, a newspaper advertisement caught her eye. It was an advertisement for Peace Boat, a Japan-based NGO offering voyages around the world and working to connect participants with people around the world. Thinking she would enjoy traveling, she immediately decided to apply for one of their voyages.

During this voyage, the boat docked at Guadalcanal and Rabaul, places where the soldiers who had spent their last night in Japan at the inn run by Toshiko’s parents lost their lives. The crew held a memorial service for the soldiers and Toshiko mourned them, recalling how they had taken good care of her.

At the time, she felt reluctant to talk about her experiences of the atomic bombing like other survivors did. In 2008, a turning point arrived when she visited Venezuela. A mayor in Venezuela said, “A-bomb survivors have an obligation to speak about what happened.” These words changed her. At the age of 70, Toshiko delivered her testimony of the atomic bombing for the first time. She did this from Venezuela, through a Latin American satellite broadcasting network called teleSUR. Starting with that time in Venezuela, she has since traveled to more than 80 countries and related her experiences to a wide range of people, including students, scientists, and scholars.

Peace begins with one encounter

In May of 2010, several hundred A-bomb survivors flew to the U.S. for the Review Conference of Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), which was held at the United Nations Headquarters in New York. After the conference, some of the survivors stayed and gave their testimonies at 25 local junior high and high schools. Toshiko had been invited to New York as a member of Hibakusha Stories. She visited a high school in Queens, where many immigrants resided.

Among the students was a boy who was originally from Palestine. He had had a difficult childhood, with family members who were killed by Israeli troops. Even after moving to the U.S., he shut his mind and continued to harbor hatred for Israel. Toshiko told him, “There must be forgiveness in order to cut the chain of hatred.” After hearing her words, the boy became more open to other perspectives. He changed, mentally, to such an extent that it surprised his teacher.

The story of Toshiko and the boy is featured in the book Yononaka e no tobira: Kiseki wa tsubasa ni notte (Doors to the World: Miracles on Wings) written by Kazuko Minamoto and published by Kodansha.

“How can you forgive the U.S. even though you were A-bombed, got burned, and lost your friends?” the boy from Palestine asked Toshiko. She was an inspiration to him.

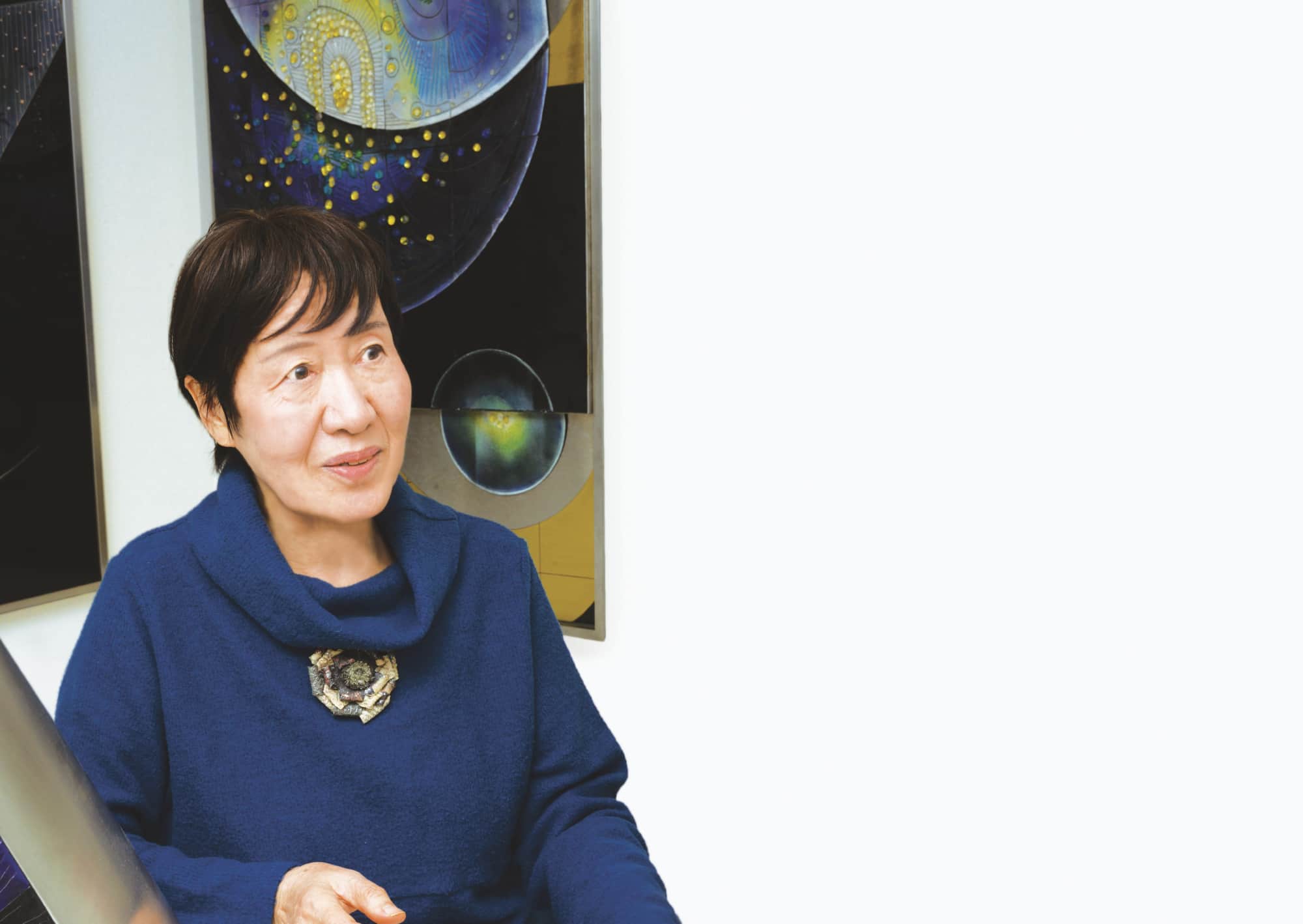

The boy with his teacher, a few years after he first met Toshiko. His encounter with Toshiko is described in the book.

Opening her home to people from all over the world

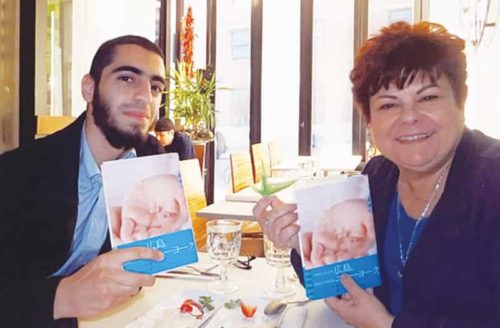

Toshiko with the family of Clifton Truman Daniel, the grandson of former U.S. president Harry S. Truman*

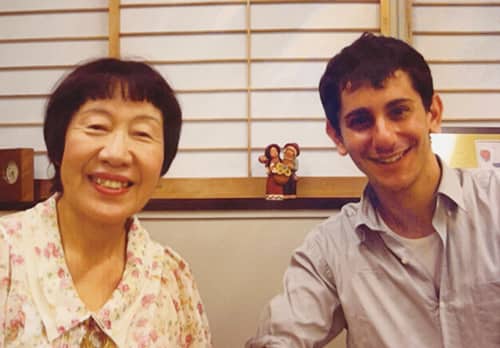

Toshiko with Ari Beser, the grandson of Jacob Beser, a crew member of Enola Gay*

Toshiko’s style of enameling has changed since she started telling her story. “Expressing only the beauty of nature isn’t enough for me,” she said. “I put symbols of peace or nuclear abolition in my pieces somewhere.” She remodeled the first floor of her house to create the “Peace Exchange Space,” a public space for peace and art exchange, with her enamel works adorning the walls. Since then, people from all over Japan and the world have visited her home. In 2012, Clifton Truman Daniel, the grandson of former U.S. president Harry S. Truman, and his family visited her. “Clifton’s wife and I made a small accessory together. She was so happy with that. That’s peace, isn’t it?” Toshiko said in delight. “There must be forgiveness in order to cut the chain of hatred.” She carries out what she taught the Palestinian boy in her daily life, based on her experiences of traveling across the world and interacting with many kinds of people. “If you make friends abroad, even when there are problems between your two countries, you wouldn’t think, ‘Just drop bombs on them.’”

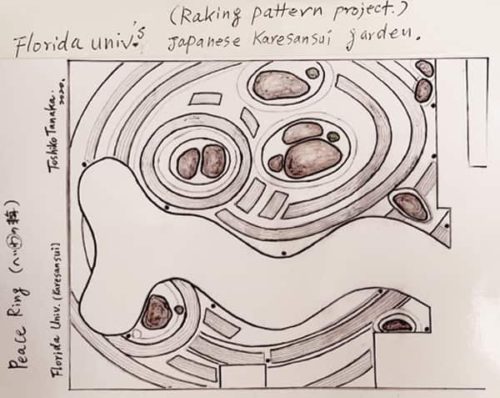

“Peace Ring”

Designed Japanese dry landscape gardens in the U.S.

Toshiko was asked to collaborate with Martin McKeller, the director of dry landscape gardens at the Harn Museum of Art in the U.S., after he spoke with Yumi Kanazaki of the Chugoku Shimbun Newspaper Company. Toshiko made the design for five Japanese dry landscape gardens in the U.S., and on International Peace Day on September 21, 2020, the gardens featured ripple marks in the sand. The Peace Ring drawing event was filmed and made into a video. The drawing event has become an official occasion of the North American Japanese Garden Association since 2021, and it now takes place in 14 locations. Gardens in nine states are engaged in Peace Ring including the Fort Worth Botanical Garden in Texas and a garden in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, a site of the Manhattan Project, which developed the first nuclear weapons. The drawing event is also held at two sites without dry landscape gardens including the Manzanar National Historic Site in California, where a relocation center for Japanese-American was located during the war. A movement promoting peace in these low-key, creative ways has been spreading in the U.S.

The idea for the drawing event was conceived by Martin McKeller of the Harn Museum of Art. He began pondering what he could do to promote peace after he was stopped by students in Kyoto on a school trip to answer a questionnaire about peace in 1998.

Toshiko’s original design. She calculated the areas of the gardens at a reduced scale and then drew the patterns representing the Japanese characters へ (He), い (I), and わ (Wa). (In Japanese, “heiwa” means “peace” and “wa” by itself means “ring.”)

I was six on that day.

I remember the blue sky I saw through the roof

amid overwhelming devastation.

It continues to encourage me

and teaches me a lesson.

“There is hope

even in dark times.”

Thinking of my late classmates,

I want to fulfill my mission

as an A-bomb survivor.

I want to spread this message

to as many people as possible:

“Nuclear weapons must not exist in the world!”

I was six on that day.

I remember the blue sky I saw through the roof

amid overwhelming devastation.

It continues to encourage me

and teaches me a lesson.

“There is hope

even in dark times.”

Thinking of my late classmates,

I want to fulfill my mission

as an A-bomb survivor.

I want to spread this message

to as many people as possible:

“Nuclear weapons must not exist in the world!”

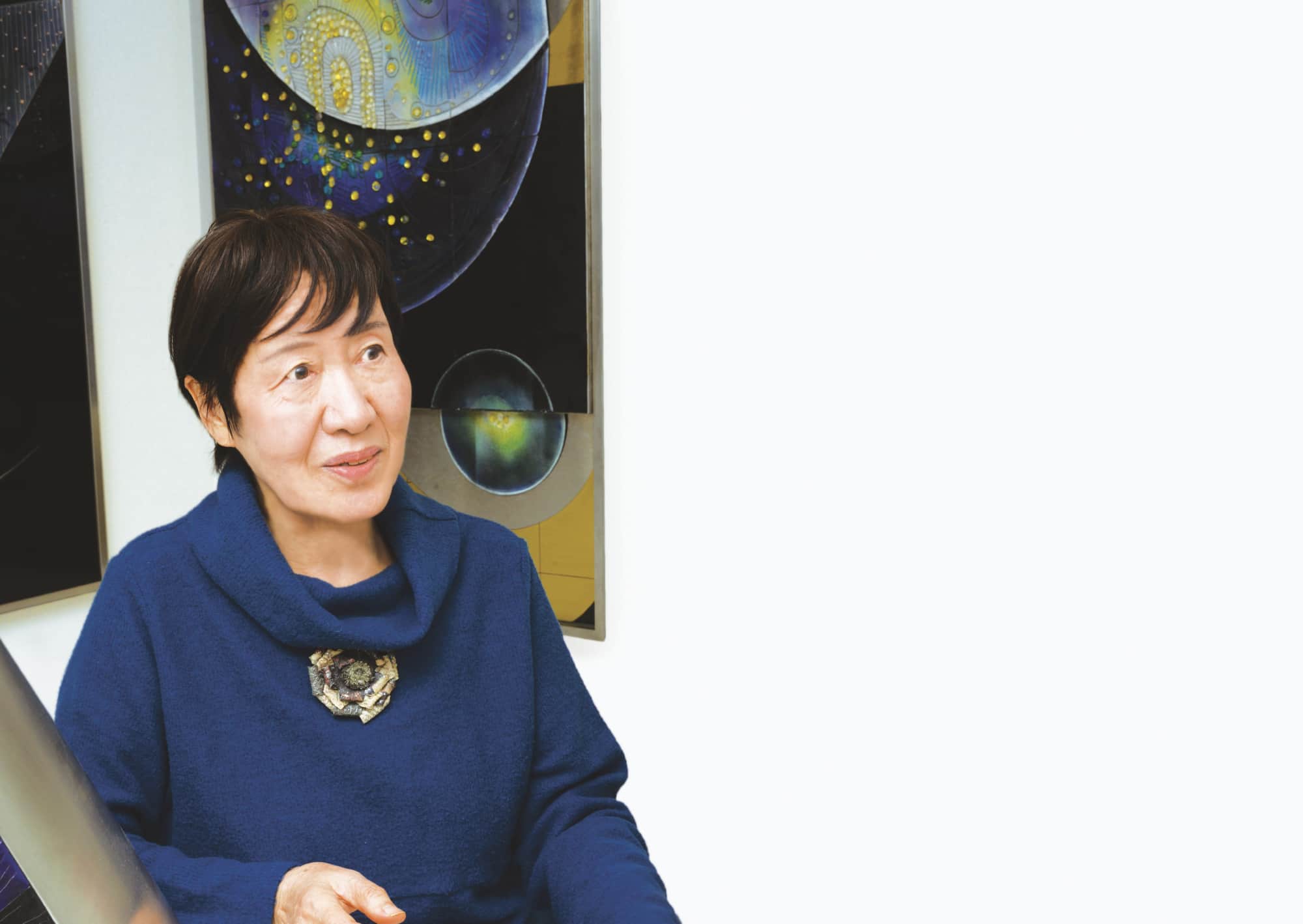

The “Peace Exchange Space” created by remodeling the first floor of her house and displaying Toshiko’s works.

Her experiences traveling throughout the world and interacting with a wide range of people are reflected in her creations and breathe deep meaning into them. Many of her pieces evoke a kind of cosmic perspective, like looking down on the earth.

The “Peace Exchange Space” created by remodeling the first floor of her house and displaying Toshiko’s works.

Her experiences traveling throughout the world and interacting with a wide range of people are reflected in her creations and breathe deep meaning into them. Many of her pieces evoke a kind of cosmic perspective, like looking down on the earth.

Edited and produced by ANT-Hiroshima

Photography by Mari Ishiko

Text by Aya Yoshimoto and Mika Goto

Translation by Aya Yoshimoto

Translation edited by Adam Beck

and Annelise Giseburt