My elder sister, who was 12 years old, went out after the air raid alert stopped in the morning that day.

Even though she cheerfully said “I’ll be home later,” she has not returned yet.

Imagine.

Imagine that a member of your family goes out, saying “I’ll be home later,” but never comes back.

My elder sister, who was 12 years old, went out after the air raid alert stopped in the morning that day.

Even though she cheerfully said “I’ll be home later,” she has not returned yet.

Imagine.

Imagine that a member of your family goes out, saying “I’ll be home later,” but never comes back.

Profile

Emiko Okada (née Nakasako)

Born in Onaga-machi Hiroshima City, on January 1, 1937.

Emiko had a family of six: father, mother, a sister four years older than her, a brother three years younger, and another brother five years younger. On August 6, 1945, Emiko was exposed to the atomic bomb at the age of eight. Her elder sister, 12 years old at the time, departed for building demolition work in the morning and never returned. Some years later, Emiko attended Hijiyama Girls Junior and Senior High Schools and entered a dressmaking school.

Emiko’s father, who had taught at Matsumoto Technical School (current Setouchi Senior High School) during the war, resigned due to the pain of losing his daughter, as well as the guilt of switching from military education to democratic education. He opened a tool store but went bankrupt over time. Emiko’s parents moved to Tokyo, relying on their son there, leaving Emiko alone in Hiroshima. To pay off her family’s debts, she opened a dressmaking store, using the skills she acquired at dressmaking school. Amid her busy life, she got married.

Emiko was eventually able to make ends meet and was blessed with two children. However, her eldest son was killed in a car accident while in his first year of junior high school. Her despair at the loss led her to step away from the fashion industry.

In 1987, when she was 50 years old, Emiko saw a newspaper article about the World Friendship Center (WFC), which was looking for people to work for peace activism in the United States, and applied for the role. She was selected to visit the US as an atomic bomb survivor and to introduce Japanese culture. In the US, she met Barbara Reynolds, who awakened Emiko to peace activism, and she began teaching herself not only about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki but also about the Sino-Japanese War, the Battle of Okinawa, the Nanjing Massacre, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, landmines, and more.

In 1999, Emiko began working with Hiroshima Peace Volunteers and started giving her testimony of the atomic bombing at the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation. In 2000, she gave her testimony in Kyiv, Ukraine, where she met victims of the Chornobyl nuclear disaster. In 2005, she traveled to India and Pakistan as a member of the Hiroshima World Peace Mission, a project to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the atomic bombing. In 2007, Emiko gave her testimony at an exhibition about the atomic bombing in the US. In 2009, she and her granddaughter traveled to New York for Emiko to give her atomic bomb testimony at the United Nations Headquarters.

She also appeared in the documentary film “Atomic Mom.” Toward the end of her life, Emiko was actively involved in the Hibakusha Appeal signature campaign and actions for the adoption of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW).

In April 2021, while attending a WFC meeting, Emiko passed away suddenly, at the age of 84.

Family photo 1

From left, Emiko’s elder sister, Emiko, younger brother, and mother.

Emiko’s father in the back.

Emiko’s elder sister, Mieko Nakasako, was 12 years old in 1945. She was a student in Hiroshima First Prefectural Girls High School, a girls’ school in Hiroshima.* Their parents were very proud of her. “We would secretly talk while hiding in curtains. We were just average sisters,” Emiko said. On the morning of August 6, Mieko passed away while working to demolish buildings to create fire breaks* in the event of an air raid.

“Mieko and her classmates assembled in the Dobashi* neighborhood,” Emiko said. “No one has any idea what my sister did or where she went after the bomb was dropped. I sincerely hope that she did not suffer, was not lost and trying to flee, in her last moments.”

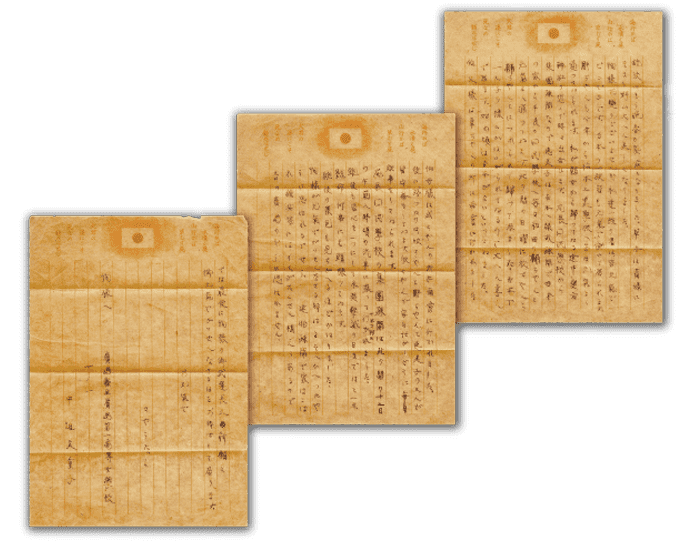

A letter from Mieko

Emiko’s parents desperately looked for any trace of Mieko, believing that she might still be alive because her body was yet to be found.

“My mother was pregnant at the time, but later had a miscarriage. I am sure my parents did not submit an official notice of Mieko’s death. That’s why her name is not engraved on the Memorial Mound,” Emiko said.

As the war progressed, young students were required to participate in building demolition work to prevent fires from spreading in potential air raids. The total number of children who passed away in the atomic bombing while dismantling buildings is estimated to be 6,000.

“Think of it — 12- and 13-year-olds are still young children. Their hats, school uniforms, buttons, school badges… Those items in the Peace Memorial Museum are not replicas; they are articles that belonged to real children. There is absolutely nothing that can justify the sacrifices of children,” Emiko said.

All that remained to Emiko of her sister was a letter Mieko had written: “Her letter, which was addressed to our cousin who went to war, was returned. This is the only article she left; everything, even her bones, are not yet found.”

“I still keep the door of my home open for my sister. For the moment that I finally say, ‘Welcome back, sister.’”

See, I was eight when the bomb was dropped.

After 12 years, I was diagnosed with aplastic anemia.

That’s when I first looked back on my past and questioned.

“What is an atomic bomb?”

“Why was the bomb dropped on Hiroshima?”

I, up to that point, was truly ignorant.

The bombing had a physical effect on Emiko. “My gums were bleeding and my hair fell out. I had to be in bed frequently due to fatigue. Back then, no one knew all these sicknesses were due to radiation,” she said. At the age of 20, Emiko was diagnosed with aplastic anaemia. Many survivors experienced similar symptoms. Health concerns extend to the second-generation of atomic bomb survivors.

See, I was eight when the bomb was dropped.

After 12 years, I was diagnosed with aplastic anemia.

That’s when I first looked back on my past and questioned.

“What is an atomic bomb?”

“Why was the bomb dropped on Hiroshima?”

I, up to that point, was truly ignorant.

The bombing had a physical effect on Emiko. “My gums were bleeding and my hair fell out. I had to be in bed frequently due to fatigue. Back then, no one knew all these sicknesses were due to radiation,” she said. At the age of 20, Emiko was diagnosed with aplastic anaemia. Many survivors experienced similar symptoms. Health concerns extend to the second-generation of atomic bomb survivors.

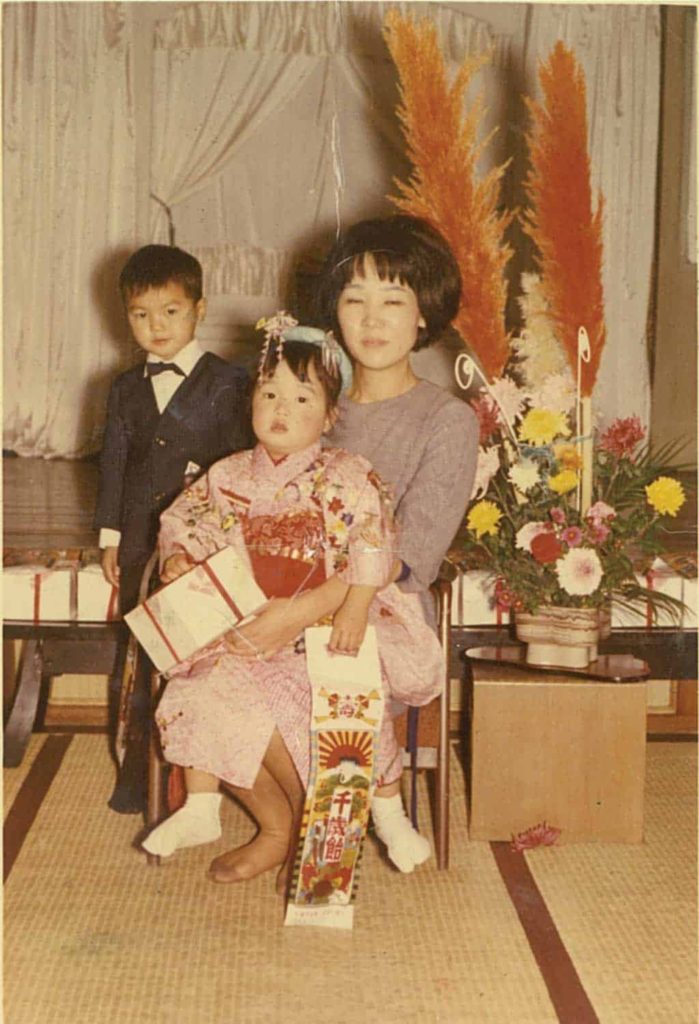

Family photo 2

Emiko married when she was 24 years old and was fortunate enough to have two children. In the difficult years after the war, she worked hard using her dressmaking skills; she eventually opened a shop in a department store. “I dreamed of building a fashion department store once my children were independent,” she said.

But one day, her dream was crushed. Her son, who was then in his first year of junior high school, passed away in a traffic accident. “I sat in front of the family Buddhist altar and drank like a fish. I got sick of seeing people at work too.” She left the fashion industry. Her next turning point would come a while later.

In celebration of children’s Shichi-go-san (a Japanese traditional festival to celebrate the growth of children). Emiko’s son, daughter, and Emiko.

Awakening to Peace Activism

Awakening to Peace Activism

Second from right is Barbara Reynolds, founder of the World Friendship Center.

Emiko is in the center.

Emiko, in the depths of despair from losing her son, kept her distance from the fashion industry. One day, while reading a newspaper, an article caught her attention. “What can you do for world peace?” it said. The World Friendship Center* was recruiting people for peace activities in the US. “Up to that point, I was just surviving. I did not have a single thought about world peace.” Emiko’s skills on her résumé — Japanese Nihon Buyo dance, tea ceremony, and Ikebana (Japanese art of flower arrangement) — caught the attention of the recruiter, and she was chosen to introduce Japanese culture. In 1987, when she was 50 years old, Emiko went to the US. This was the starting point of her peace activism.

When she talked about her experiences of the atomic bombing in the US, some among the listeners would always reply “Pearl Harbour came first.” Emiko started learning more about the atomic bombings and wars in other countries.

I am a survivor of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

However, my peace activism is not limited to merely talking about my experiences of the bombing and the tragedy of Hiroshima.

Today, everyone around the world is at risk of becoming the next victim.

I am a survivor of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

However, my peace activism is not limited to merely talking about my experiences of the bombing and the tragedy of Hiroshima.

Today, everyone around the world is at risk of becoming the next victim.

Sharing her A-bomb testimony in Kyiv, Ukraine

Emiko giving a talk with a map in her hands.

In 2000, Emiko visited the capital of Ukraine, Kyiv, with Mr. Hitoshi Kai from the Junod Association.* The association is named after Dr. Marcel Junod (1904-1961), a Swiss physician who delivered medical supplies to Hiroshima after the bombing and treated survivors.

Emiko was given the opportunity to represent atomic bomb survivors and give a talk to victims of the Chornobyl disaster. The hall contained many pictures of children who had passed away due to the accident. Although Kyiv is nearly 10 kilometers from the Chornobyl nuclear power plant, many of the students at a nearby primary school were suffering from thyroid cancer. “Innocent children must never be sacrificed,” Emiko said. Her painful memories of losing her sister and son channeled into a strong love towards children around the world.

Hiroshima and Ukraine are linked by their shared experiences of radiation damage. The fact that Emiko, an atomic bomb survivor, survived the devastation of the bombing and visited Kyiv must have given hope to the people there.

To the United Nations with her granddaughter

In 2009, Emiko attended a conference at the United Nations Headquarters in New York with her granddaughter. They each gave speeches to representatives and mayors from countries across the world. “Mayors from various countries talked to my granddaughter; I thought to myself, this is peace,” Emiko said.

Spontaneous applause broke out. Emiko sincerely felt that peace was a product of conversation.

From these experiences, when Emiko gave talks about the atomic bombing, she always incorporated what she saw outside of Hiroshima and other issues related to nuclear weapons, keeping her global perspective.

When President Obama visited Hiroshima, a reporter asked me, “Do you want Mr. Obama to apologize?”

I answered, “If it could make my sister come back, I would want Mr. Obama to apologize.”

See, my sister never came back.

The past is the past, what is done is done.

But the future is in our hands.

Isn’t it?

On May 27, 2016, 44th US President Barack Obama visited Hiroshima. It was the first time in history that a sitting president of the US, the country that dropped the atomic bomb, visited Hiroshima. The visit drew the world’s attention.

Edited and produced by ANT-Hiroshima

Photography by Mari Ishiko

Text by Mika Goto

Translation by Noa Seto

Translation edited by Annelise Giseburt