August 6, 1945, 8:15 a.m.

1.1 kilometers from the hypocenter

A parsonage near Hiroshima Nagarekawa Church collapsed as the atomic bomb exploded.

I, eight months old, miraculously survived in my mother’s arms.

I escaped death, and my battle began at this exact moment.

August 6, 1945, 8:15 a.m.

1.1 kilometers from the hypocenter

A parsonage near Hiroshima Nagarekawa Church collapsed as the atomic bomb exploded.

I, eight months old, miraculously survived in my mother’s arms.

I escaped death, and my battle began at this exact moment.

-

Profile

Koko Kondo

Koko Kondo (née Tanimoto)

Koko was born on November 20, 1944 (Showa 19), as the eldest daughter of father Kiyoshi Tanimoto, reverend of Hiroshima Nagarekawa Church, and mother Chisa. On August 6, 1945, eight months after her birth, Koko was exposed to the atomic bomb in the church’s parsonage, 1.1 kilometers from the hypocenter. She was trapped under the collapsed building but miraculously survived, protected by her mother’s arms.

After the war, Koko’s father devoted himself to helping hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors), who carried both physical and emotional scars. As a young child, Koko often felt lonely as her father travelled around Japan and abroad and was rarely at home. During this time, she interacted with children orphaned by the atomic bomb who had nowhere to go and who came to the church seeking mental and physical salvation, and with young women who had suffered severe burns to their faces and were called “Hiroshima Maidens.” Witnessing the anguish of these orphans and women made Koko grow to hate the United States for dropping the atomic bomb on them.

On the other hand, through her father, Koko grew up also knowing Americans dedicated to the revitalisation of Hiroshima. They included Mr. John Hersey (1914-1993), a journalist who published the longform article “Hiroshima” — which became a huge bestseller — and made the name “Kiyoshi Tanimoto” well-known in the United States; Ms. Pearl Buck (1892-1973), a Nobel Prize-winning author who supported Reverend Tanimoto’s peace activism from its early stages; and Mr. Norman Cousins (1915-1990), a member of the Hiroshima Peace Center Associates, who became acquainted with Reverend Tanimoto through them. All these people affectionately doted on the young Koko.

When she was in junior high school, Koko visited the ABCC (Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission, now the Radiation Effects Research Foundation) for a medical examination. She felt unbearable humiliation when she had to remove her gown and expose her naked upper body in front of several adults. Seeking a life where she would no longer be labelled “hibakusha,” Koko decided to attend J.F. Oberlin Senior High School in Tokyo by herself. After graduating from high school, she studied abroad in the US. During her five and a half years there, she became friends with Peal Buck and was profoundly influenced by her. She graduated from Centenary College for Women in 1966 and from American University in 1969. After returning to Japan in the same year, she worked as a secretary at a foreign-affiliated company in Tokyo for a while.

At the age of 30, Koko married Yasuo Kondo, who later became a minister. They moved from Tokyo to Hiroshima to help with the work at the Hiroshima Peace Center, run by her father, Reverend Tanimoto, at Nagarekawa Church. Since then, Koko has worked as an interpreter for foreign visitors to Hiroshima and given testimonies in Japan and abroad about her experience of the atomic bombing and life after. Since 1996, she has taken Japanese and American university students from Ritsumeikan University and her alma mater, American University, to attend the Peace Memorial Ceremonies in Hiroshima on August 6 and in Nagasaki on August 9 every year.

Koko has devoted herself to “international adoption” for more than half a century, connecting children in Japan who need a home with adoptive parents abroad. She also serves as an international relations advisor for Children as the Peacemakers, a US foundation that advocates for peace together with children around the world.

Koko’s Childhood — Daughter of Reverend Tanimoto, who was dedicated to helping hibakusha

Koko’s Childhood

— Daughter of Reverend Tanimoto, who was dedicated to helping hibakusha

▲Hiroshima Nagarekawa Church after the atomic bombing.

Although the city of Hiroshima was completely destroyed, Koko miraculously survived.

◀︎Hiroshima Nagarekawa Church after the atomic bombing.

Although the city of Hiroshima was completely destroyed, Koko miraculously survived.

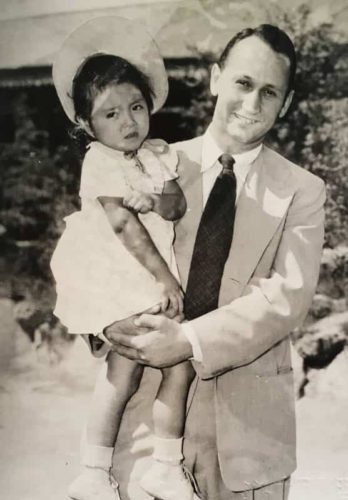

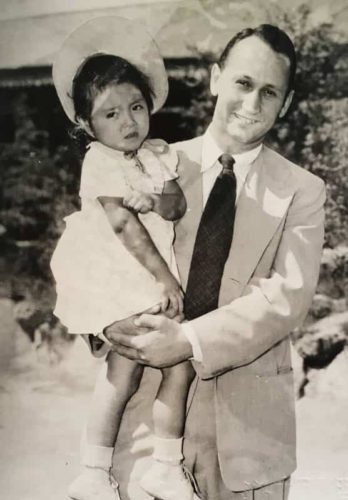

October 1, 1949. This photo commemorates the completion of the Minami-machi Peace House. It was built by Mr. Floyd Schmoe and his friends. Koko is in the center, in the arms of Mr. Schmoe.▼

Floyd Schmoe

To apologise for the atomic bombings and to serve the people who had lost their homes, Floyd Schmoe built 21 houses and community centers in Hiroshima and Nagasaki from 1949 to 1953 for hibakusha, funded by donations from around the world. They were affectionately known as “Hiroshima Houses.”

Floyd Schmoe

To apologise for the atomic bombings and to serve the people who had lost their homes, Floyd Schmoe built 21 houses and community centers in Hiroshima and Nagasaki from 1949 to 1953 for hibakusha, funded by donations from around the world. They were affectionately known as “Hiroshima Houses.”

▲October 1, 1949. This photo commemorates the completion of the Minami-machi Peace House. It was built by Mr. Floyd Schmoe and his friends. Koko is in the center, in the arms of Mr. Schmoe.

Reverend Tanimoto and his fellows organizing supplies that arrived from around the world to Hiroshima after the atomic bombing. Young Koko can also be seen in the photo.

Koko in the arms of Mr. Norman Cousins, who was close with Koko’s father, Reverend Tanimoto.▼

▲Reverend Tanimoto and his fellows organizing supplies that arrived from around the world to Hiroshima after the atomic bombing. Young Koko can also be seen in the photo.

Norman Cousins

An American author, editor, and journalist. As a member of Hiroshima Peace Center Associates, he was dedicated to supporting the “spiritual adoption” of atomic bomb orphans by American foster parents and the medical treatment of the “Hiroshima Maidens” in the US. In 1964, he became a special honorary citizen of Hiroshima.

Norman Cousins

An American author, editor, and journalist. As a member of Hiroshima Peace Center Associates, he was dedicated to supporting the “spiritual adoption” of atomic bomb orphans by American foster parents and the medical treatment of the “Hiroshima Maidens” in the US. In 1964, he became a special honorary citizen of Hiroshima.

▲Koko in the arms of Mr. Norman Cousins, who was close with Koko’s father, Reverend Tanimoto.

▲A photo of Koko’s family: Koko’s father, Mr. Kiyoshi Tanimoto, her mother Chisa, her younger brother and younger sister. Koko is on the right. Her youngest brother was yet to be born.

▲After the war, Nagarekawa Church was rebuilt. Nagarekawa Kindergarten was also established within its premises.

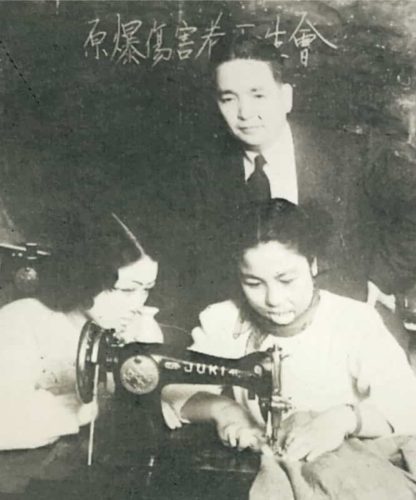

Various issues faced by hibakusha were discussed at the Hiroshima A-bomb Victims Rehabilitation Society, which was established in 1951. At the urging of Reverend Tanimoto, women who had suffered keloids from burns caused by the atomic bomb gathered together and, using donated sewing machines, aimed to support themselves through dressmaking.

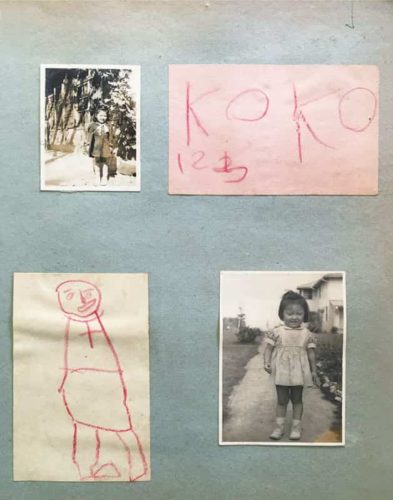

▲From Koko’s photo album.

We can catch a glimpse into Koko’s upbringing from “KOKO” written in English and a portrait with a cross on the chest.

▲Various issues faced by hibakusha were discussed at the Hiroshima A-bomb Victims Rehabilitation Society, which was established in 1951. At the urging of Reverend Tanimoto, women who had suffered keloids from burns caused by the atomic bomb gathered together and, using donated sewing machines, aimed to support themselves through dressmaking.

Hiroshima Peace Center and Hiroshima Peace Center Associates

Kiyoshi Tanimoto became known throughout the United States with the publication of John Hershey’s longform article “Hiroshima” in The New Yorker in 1946. Two years later, in September 1948, Mr. Tanimoto traveled to the US. He gave lectures in 256 cities across 31 states over the next 15 months, explaining the devastation of Hiroshima and the importance of peace. Between lectures, Mr. Tanimoto stressed the need for a “Hiroshima Peace Center,” a hub for providing care for hibakusha and communicating peace. Ms. Pearl Buck, an author and social activist, agreed with his idea. With the cooperation of Norman Cousins, with whom Mr. Tanimoto had become friends through Buck’s introduction, the Hiroshima Peace Center was established in Hiroshima and the Hiroshima Peace Center Association was established in New York. Through the immense support of the Association, Mr. Tanimoto conducted the “spiritual adoption” of atomic bomb orphans by American foster parents and the medical treatment of the “Hiroshima Maidens” in the US. The center still exists today and continues to avocate for peace by awarding the Kiyoshi Tanimoto Peace Prize and holding the World Peace Speech Contest.

I felt a sincere hatred when I was young.

The atomic bomb that burned the soft skin of young women,

the airplane that dropped the bomb on Hiroshima,

and the pilot who aimed at his target.

“I will never forgive. Someday I will take revenge on my enemies!”

Then, I met him when I was 10.

He was driven to tears, suffering from extreme guilt for committing an irrevocable crime.

My God!

At that exact moment, my clenched fist opened.

I felt a sincere hatred when I was young.

The atomic bomb that burned the soft skin of young women,

the airplane that dropped the bomb on Hiroshima,

and the pilot who aimed at his target.

“I will never forgive. Someday I will take revenge on my enemies!”

Then, I met him when I was 10.

He was driven to tears, suffering from extreme guilt for committing an irrevocable crime.

My God!

At that exact moment, my clenched fist opened.

-

Story.1

Koko Kondo

“Koko-chan, Koko-chan!”

As a child, Koko was treated like a younger sister by the young ladies who came to her church. However, Koko, four years old at the time, had a certain problem. “Their eyes, noses, lips, chins … Their faces were covered with severe keloids. As a young girl, I was too scared to look directly at their faces. I did not know where to look.” As she interacted with the women, Koko gradually developed a hatred for the atomic bomb that had damaged their bodies. “I will never forgive the pilots who dropped the bomb. If I ever meet them, I will take my revenge,” she thought at the time.

When she was 10, Koko unexpectedly got her wish.

She, along with her family, appeared on an American TV show called “This is Your Life” with the recommendation of the Hiroshima Peace Center in order to collect funds for keloid treatment.

A screen was quickly removed, and a tall white man in a suit appeared in the studio.

“Who is he?” Koko asked her mom.

“Koko, that’s the co-pilot who dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima,” she replied. That man was Koko’s longtime “nemesis”: Robert Lewis, co-pilot on the Enola Gay, the US military plane that had dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

The climax of the program that day was a face-to-face meeting between Kiyoshi Tanimoto, Koko’s father who had dedicated his life to helping hibakusha, and Captain Lewis, one of the men who dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

The time had finally come! The person Koko had always hated was right in front of her. If it hadn’t been for him…! Koko fought the urge to immediately punch him and continued to glare.

But his next words shocked her. “My God, what have we done?” Captain Lewis explained the words he had written down in his flight log as the Enola Gay circled back over a Hiroshima that had disappeared. Tears were in his eyes as he spoke in a choked voice.

Koko was struck by his tears. “This man who had been my enemy was also dealing with guilt, sorrow, and pain,” she thought. She approached him and held his large, warm hand.

“We all have evil in us. It is not him that I should hate. It is the weakness of people who start wars that we should hate,” she realized. In that moment, Koko overcame her hatred.

On May 27, 2016, Barack Obama became the first sitting US president to visit Hiroshima. In his speech, he said, “One woman forgave the pilot who dropped the bomb.” It is said that he was referring to Koko and Captain Lewis.

-

Story.1

Koko Kondo

“Koko-chan, Koko-chan!”

As a child, Koko was treated like a younger sister by the young ladies who came to her church. However, Koko, four years old at the time, had a certain problem. “Their eyes, noses, lips, chins … Their faces were covered with severe keloids. As a young girl, I was too scared to look directly at their faces. I did not know where to look.” As she interacted with the women, Koko gradually developed a hatred for the atomic bomb that had damaged their bodies. “I will never forgive the pilots who dropped the bomb. If I ever meet them, I will take my revenge,” she thought at the time.

When she was 10, Koko unexpectedly got her wish.

She, along with her family, appeared on an American TV show called “This is Your Life” with the recommendation of the Hiroshima Peace Center in order to collect funds for keloid treatment.

A screen was quickly removed, and a tall white man in a suit appeared in the studio.

“Who is he?” Koko asked her mom.

“Koko, that’s the co-pilot who dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima,” she replied. That man was Koko’s longtime “nemesis”: Robert Lewis, co-pilot on the Enola Gay, the US military plane that had dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

The climax of the program that day was a face-to-face meeting between Kiyoshi Tanimoto, Koko’s father who had dedicated his life to helping hibakusha, and Captain Lewis, one of the men who dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

The time had finally come! The person Koko had always hated was right in front of her. If it hadn’t been for him…! Koko fought the urge to immediately punch him and continued to glare.

But his next words shocked her. “My God, what have we done?” Captain Lewis explained the words he had written down in his flight log as the Enola Gay circled back over a Hiroshima that had disappeared. Tears were in his eyes as he spoke in a choked voice.

Koko was struck by his tears. “This man who had been my enemy was also dealing with guilt, sorrow, and pain,” she thought. She approached him and held his large, warm hand.

“We all have evil in us. It is not him that I should hate. It is the weakness of people who start wars that we should hate,” she realized. In that moment, Koko overcame her hatred.

On May 27, 2016, Barack Obama became the first sitting US president to visit Hiroshima. In his speech, he said, “One woman forgave the pilot who dropped the bomb.” It is said that he was referring to Koko and Captain Lewis.

Alone on a stage,

The light shines on me as I stand still.

From the darkness on the other side came a voice.

“Take off your gown.”

Exposed in just my underwear,

I felt humiliated, angry, frustrated, sad …

I am not the one who started the war!

So why do I have to go through this?

That’s when I made up my mind:

I’ve had enough! I am leaving Hiroshima!

As long as I live, I will never tell anyone that I was exposed to the atomic bomb in Hiroshima.

The Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC, now the Radiation Effects Research Foundation), established by the United States in 1947 to study the effects of the atomic bombings on the human body, was conducting follow-up studies on the health of infants and young children as well as adults. Koko had been receiving regular examinations once or twice a year since she was a child, but when she went for her usual examination as a junior high school student, she was taken to a large, auditorium-like room where the doctor instructed her to wear only her underwear. Tears fell from Koko’s eyes as she prayed, “God, please get me out of here right now,” but no help was forthcoming. “Let me leave Hiroshima…!” Koko decided to go to high school in Tokyo. For a long time, she did not even tell her family about this humiliating experience.

Alone on a stage,

The light shines on me as I stand still.

From the darkness on the other side came a voice.

“Take off your gown.”

Exposed in just my underwear,

I felt humiliated, angry, frustrated, sad …

I am not the one who started the war!

So why do I have to go through this?

That’s when I made up my mind:

I’ve had enough! I am leaving Hiroshima!

As long as I live, I will never tell anyone that I was exposed to the atomic bomb in Hiroshima.

The Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC, now the Radiation Effects Research Foundation), established by the United States in 1947 to study the effects of the atomic bombings on the human body, was conducting follow-up studies on the health of infants and young children as well as adults. Koko had been receiving regular examinations once or twice a year since she was a child, but when she went for her usual examination as a junior high school student, she was taken to a large, auditorium-like room where the doctor instructed her to wear only her underwear. Tears fell from Koko’s eyes as she prayed, “God, please get me out of here right now,” but no help was forthcoming. “Let me leave Hiroshima…!” Koko decided to go to high school in Tokyo. For a long time, she did not even tell her family about this humiliating experience.

-

Story.2

Koko Kondo

After graduating from high school in Tokyo, Koko studied in the US for five and a half years, never returning to Japan during that time, and working hard at her studies while earning a scholarship. It was during her study abroad that she deepened her relationship with Pearl Buck, the Nobel Prize-winning author whom she admires as her “second mother.” Pearl Buck, who was a supporter of the Hiroshima Peace Center founded by Koko’s father, Kiyoshi, had adopted and raised children herself, including war orphans, and had devoted her personal wealth to protecting the rights of children of mixed heritage born to American soldiers and local women during the Korean War. “For all children, regardless of the circumstances they were born under, it is a pure miracle that they were born into this world,” she said. Her words and actions became etched deep in Koko’s heart and continued to serve as guiding principles for her life.

Blessed with friends, Koko had a fulfilling youth overseas. However, in her senior year of college, just before her graduation, she once again fell under the curse of Hiroshima. She fell in love with a young American man she met there and agreed to become engaged to him, partly because she had been holding on to the feeling that she did not want to return to Hiroshima due to the emotional trauma she had suffered at ABCC.

However, her fiancé’s uncle, who was a doctor, opposed their marriage. “A girl who was exposed to the atomic bomb near the hypocenter in Hiroshima would never be able to give birth to a healthy child,” he argued.

Koko had run and run, and even though she had come such a long way, across the ocean, Hiroshima followed her everywhere. In the end, they broke off their engagement. Koko was deeply hurt again, but at the same time, the image of the “young women” flashed through her mind.

The young women with severe keloids on their faces, who would gently comb Koko’s hair when she was a little girl. The young, kind women who would look at their fingers, seared together with keloids, and say, “Because of this body, I wasn’t able to marry my fiancé.”

“Although I am hurting right now, those women must have felt worse,” Koko reflected. She felt a strange feeling, as if she could deeply sympathize and lean into the suffering of these women.

This incident spurred Koko to return to Japan after graduating from university. After working in Tokyo for a while, she and her husband, whom she married at the age of 30, returned to Hiroshima in 1976, in response to her father Kiyoshi’s strong wish that she help with peace activism in Hiroshima.

By that time, the sense of resistance Koko had felt toward her hometown, which she desperately longed to leave, was slowly fading. She had also gradually begun to feel closer to her father, although she had previously felt uncared for as a daughter because he was always traveling around the world for peace activism.

“Had I been running away, avoiding facing the atomic bombing?” she wondered. The people she had met and the time that passed brought about a change in Koko’s mind. “I will not run away anymore. I was born here, so I will do what I have to do.”

Koko lived with her husband, who became a minister a few years after their marriage, in Miki City, Hyogo Prefecture, for many years while her husband served at Miki Shijimi Church. Following his retirement, they returned to Hiroshima once again. Koko continues to advocate for nuclear abolition in Japan and abroad.

-

Story.2

Koko Kondo

After graduating from high school in Tokyo, Koko studied in the US for five and a half years, never returning to Japan during that time, and working hard at her studies while earning a scholarship. It was during her study abroad that she deepened her relationship with Pearl Buck, the Nobel Prize-winning author whom she admires as her “second mother.” Pearl Buck, who was a supporter of the Hiroshima Peace Center founded by Koko’s father, Kiyoshi, had adopted and raised children herself, including war orphans, and had devoted her personal wealth to protecting the rights of children of mixed heritage born to American soldiers and local women during the Korean War. “For all children, regardless of the circumstances they were born under, it is a pure miracle that they were born into this world,” she said. Her words and actions became etched deep in Koko’s heart and continued to serve as guiding principles for her life.

Blessed with friends, Koko had a fulfilling youth overseas. However, in her senior year of college, just before her graduation, she once again fell under the curse of Hiroshima. She fell in love with a young American man she met there and agreed to become engaged to him, partly because she had been holding on to the feeling that she did not want to return to Hiroshima due to the emotional trauma she had suffered at ABCC.

However, her fiancé’s uncle, who was a doctor, opposed their marriage. “A girl who was exposed to the atomic bomb near the hypocenter in Hiroshima would never be able to give birth to a healthy child,” he argued.

Koko had run and run, and even though she had come such a long way, across the ocean, Hiroshima followed her everywhere. In the end, they broke off their engagement. Koko was deeply hurt again, but at the same time, the image of the “young women” flashed through her mind.

The young women with severe keloids on their faces, who would gently comb Koko’s hair when she was a little girl. The young, kind women who would look at their fingers, seared together with keloids, and say, “Because of this body, I wasn’t able to marry my fiancé.”

“Although I am hurting right now, those women must have felt worse,” Koko reflected. She felt a strange feeling, as if she could deeply sympathize and lean into the suffering of these women.

This incident spurred Koko to return to Japan after graduating from university. After working in Tokyo for a while, she and her husband, whom she married at the age of 30, returned to Hiroshima in 1976, in response to her father Kiyoshi’s strong wish that she help with peace activism in Hiroshima.

By that time, the sense of resistance Koko had felt toward her hometown, which she desperately longed to leave, was slowly fading. She had also gradually begun to feel closer to her father, although she had previously felt uncared for as a daughter because he was always traveling around the world for peace activism.

“Had I been running away, avoiding facing the atomic bombing?” she wondered. The people she had met and the time that passed brought about a change in Koko’s mind. “I will not run away anymore. I was born here, so I will do what I have to do.”

Koko lived with her husband, who became a minister a few years after their marriage, in Miki City, Hyogo Prefecture, for many years while her husband served at Miki Shijimi Church. Following his retirement, they returned to Hiroshima once again. Koko continues to advocate for nuclear abolition in Japan and abroad.

With unerasable “Hiroshima” inside of me

▲From when Koko flew to the US to appear on the American TV show “This is your life.”

◀︎From when Koko flew to the US to appear on the American TV show “This is your life.”

Photo taken at the residence of Pearl Buck, who was a close friend of Koko’s father, Reverend Tanimoto, after her appearance on the program. Front row, third from left, is Pearl Buck; right is Koko.▼

Pearl Buck

An American author. Having spent the earlier half of her life in China, she wrote many works set in China, such as The Good Earth. Buck received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1938. In 1949, she founded a foster home for orphans named the “Welcome House,” which helped her organize numerous adoptions.

Pearl Buck

An American author. Having spent the earlier half of her life in China, she wrote many works set in China, such as The Good Earth. Buck received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1938. In 1949, she founded a foster home for orphans named the “Welcome House,” which helped her organize numerous adoptions.

▲Photo taken at the residence of Pearl Buck, who was a close friend of Koko’s father, Reverend Tanimoto, after her appearance on the program. Front row, third from left, is Pearl Buck; right is Koko.

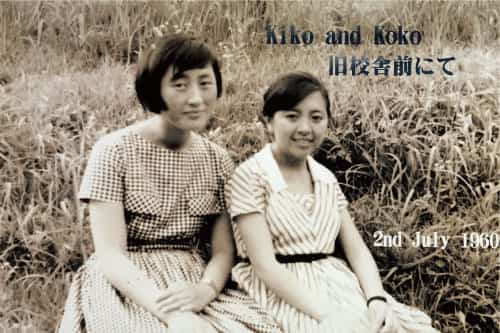

▲Photo taken when Koko (right) was in J.F.Oberlin Senior High School

Photo taken when Koko (left) was in Noboricho Junior High School

▲Photo taken when Koko (left) was in Noboricho Junior High School

▲Photo taken when Koko was in Centenary College for Women

◀︎Photo taken when Koko was in Centenary College for Women

▼Koko working in a foreign-affiliated corporation in Tokyo

▲Koko working in a foreign-affiliated corporation in Tokyo

Koko’s new life started when she stopped looking away and embraced herself

With her husband and daughters

▲With her husband and daughters

▲Koko works as International Relations Advisor for the foundation Children as the Peacemakers

◀︎Koko works as International Relations Advisor for the foundation Children as the Peacemakers

Koko holds a copy of John Hersey’s best-selling book “Hiroshima,” originally published as a longform article on Hiroshima after the atomic bombing, in which her father, Reverend Tanimoto, and Koko also appear. She continues to receive requests to speak at various locations and is very active in her work.▼

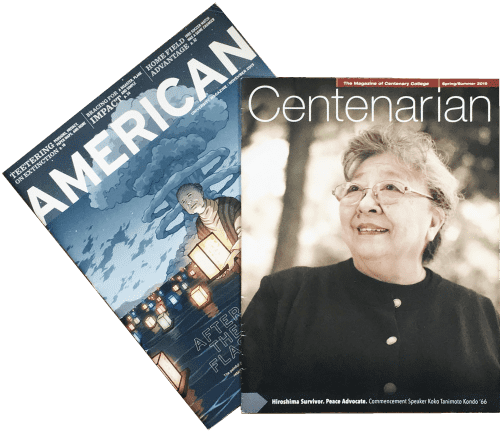

▲The school magazines of her two alma maters, Centenary College for Women and American University, featured Koko and Hiroshima.

▲In 2018, Koko received the “Tribeca Disruptive Innovation Award,” presented to individuals who have had an innovative impact on society.

▲Koko holds a copy of John Hersey’s best-selling book “Hiroshima,” originally published as a longform article on Hiroshima after the atomic bombing, in which her father, Reverend Tanimoto, and Koko also appear. She continues to receive requests to speak at various locations and is very active in her work.

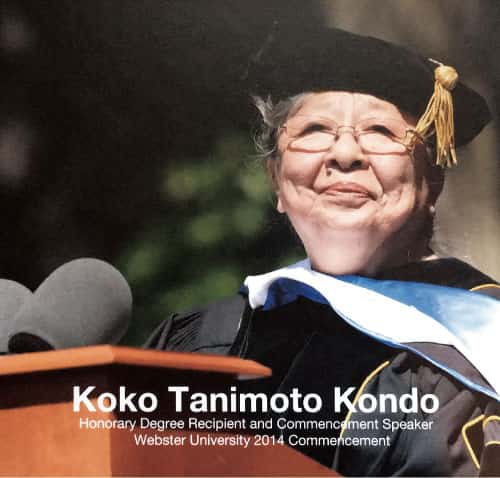

▲In 2014, Koko was invited to speak at Webster University in Missouri, US.

-

Story.3

Koko Kondo

Guided by Pearl Buck, who dedicated herself to protecting the rights of children who were born amid war and in need of a home, and also her father Kiyoshi, who devoted himself to “spiritual adoption” activities while Hiroshima still lay in ruins, Koko has been using her knowledge of early childhood education, child psychology, and law, which she learned at university in the US, to serve as an intermediary caretaker in “ international adoption*.”

“Koko, in the future, I want you to do something for children who have been victimized by the actions of adults,” Koko was once told by Pearl Buck, her “second mother” and who wished to save as many children as possible and then took steps towards that goal.

With Pearl’s words in her heart, Koko takes care of children who have suffered deep emotional trauma as a result of abuse and other forms of violence, and she devotes herself to each one of them by sharing meals, chatting, and enjoying activities together.

After spending time together and much thought if she thinks it is best for the child, Koko will introduce them to adoptive parents overseas. “The adopted children I have sent away are like my own children,” she says. “All of them are my precious children.”

Even after all these years, Koko continues to be adored as “Aunty Koko” by the children who have left her for their new homes. In her mind, she always remembers the A-bomb orphans and scarred young women she spent time with as a child.

“I was exposed to the atomic bomb when I was an infant and miraculously survived, and I have come this far thanks to countless people. This is my way of returning the favor. These children who are asking for help are my own reflection, crying out under the mushroom cloud.”

Koko has also welcomed two girls into her family and has raised them with great care. “My daughters are my pride and joy. I am so grateful to have met them,” she said.

“Koko is our child.”

Many amazing adults took care of young me as if I was their own child.

I learned from them. I learned how to love others like close kin. I learned how precious it is to connect with hearts.

Thinking of each other, complementing each other, without blaming anyone.

Person to person.

If each of us becomes a peacemaker, the evil shall not be repeated.

“Koko is our child.”

Many amazing adults took care of young me as if I was their own child.

I learned from them. I learned how to love others like close kin. I learned how precious it is to connect with hearts.

Thinking of each other, complementing each other, without blaming anyone.

Person to person.

If each of us becomes a peacemaker, the evil shall not be repeated.

Edited and produced by ANT-Hiroshima

Photography by Mari Ishiko

Text by Emi Ikeda and Mika Goto

Translation by Noa Seto

Translation edited by Annelise Giseburt